“No man is more unhappy than he who never faces adversity. For he is not permitted to prove himself.”

Seneca

If you’re reading this, chances are good that you woke up this morning in a country that isn’t in some constant state of emergency or war. You probably have access to clean drinking water, clean clothing, a physician, a supermarket, and at least some opportunity for employment.

You’re also likely not starving and you have some kind of roof over your head. And as a bonus, because of the miracle of modern medicine, odds are you won’t die of rabies, or tetanus, or polio, or whooping cough, or measles, or smallpox, or the plague. So that’s fun!

To put it into perspective, it’s sobering to remember that at this very moment, there are at least one billion people in the world who would love to trade places with you right now. One billion. With a B.

You’d think we’d be counting our blessings everyday. But, like a spoiled child, we just take everything for granted instead.

We live in a society where the perceived emotional distress we receive from some micro-aggression has a bigger impact on us than the fact that our most vital requirements for survival are being met.

In economics, that’s called the paradox of value, or the diamond-water paradox. It is the contradiction that, despite water being essential for life, diamonds fetch a higher market price.

I’ll give you an example. Think about the last time someone was rude to you. Do you remember how you reacted? How it made you feel?

If you’re like most people, the situation still lingers in your thoughts. You can remember every detail about it. You’ve repeated the story to your friends and family and it amazes you how some people can be so insensitive.

Now, what would you say if I told you that you get to sleep in a warm bed tonight? You probably wouldn’t even bat an eye. So what? You’ve always had a warm bed to sleep in.

But what would happen if your bed suddenly disappeared? Do you think you would care about that rude person anymore? I doubt it, your only concern would be with finding somewhere to sleep.

So why aren’t we grateful for our bed everyday? Why is it only when something is taken away that it concerns us?

And why does the absence of a non-essential thing have a greater impact on our mood than the presence of an essential thing?

Hierarchy of Needs

In 1943, the psychologist Abraham Maslow presented his theory of human motivation that we call Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. It’s here we might find some answers.

Maslow argued that the needs at the bottom of the pyramid needed to be met before we become motivated to pursue the needs on the higher levels.

So once your bed is taken away, your physiological needs take precedence, and therefore, trump all of your other problems.

But what happens when all of our basic needs are consistently being met?

There is a concept called the Law of Familiarity, and it states that if we are around something long enough, we tend to take it for granted. So accordingly, if our needs on a given level are being met frequently enough, we might take them for granted and look higher for sources of happiness or fulfilment.

I used the following quote in my last post, so it might sound familiar. I think there is something significant here. It might help explain further the paradox of value and our behaviour regarding our hierarchy of needs.

“There is neither happiness nor misery in the world; there is only the comparison of one state with another, nothing more. He who has felt the deepest grief is best able to experience supreme happiness. We must have felt what it is to die, that we may appreciate the enjoyments of life.”

ALEXANDER Dumas

So if happiness is relative, and if we take for granted the first two levels on the hierarchy for example, then not having love or a sense of belonging can become our primary source of misery if we don’t have a greater misfortune to compare it to.

I had been thinking about this idea while I was reading some interesting articles online.

One such article claimed that surfing had a diversity problem. The author argued that the sport was over populated with straight white men who “fuelled misogyny and homophobia” by”dominating” the waves.

By the way, I’m not making this up.

Another article asked their readers: “Will curing the deaf lead to a ‘cultural genocide’? This one in particular came from The Kennedy Institute of Ethics at Georgetown University. They claim that the deaf are a distinct ethnic group and they would be losing their cultural identity if cured.

Finally, I recently saw this headline: “Are masks giving men a licence to leer? Women report a rise in ‘aggressive eye contact’ since face coverings become commonplace as an expert warns they ‘provide anonymity’ for threatening behaviour”.

It seems as if these authors have little else to worry about if aggressive eye contact is the extent of their troubles.

It amazes me how far some of these people will go to find some form of injustice in the world that they think needs to be addressed. It’s gross. Our culture is obsessed with the ‘virtuous’ pursuit of liberating ‘oppressed’ ‘victims’

This idea is harmful for a few reasons.

Firstly, by allowing people and groups to place blame on something outside their control, they’re denied the ability and potential to change their situation on their own.

Secondly, if we take Dumas’ quote to be true, and we understand the goal of social justice -that being equity for all- then we are unknowingly inhibiting our potential to be happy by allowing individuals to take for granted the higher levels on the hierarchy.

To put simply, if we try to remove and eradicate every single misery or injustice in the world, then anything short of pure emotional bliss will be thought of as excruciating.

Life’s suffering is not distributed equally or fairly, so teaching a society to be offended by the slightest instance of inequality is not going to end well.

“What would have become of Hercules, do you think, if there had been no lion, hydra, stag or boar – and no savage criminals to rid the world of? What would he have done in the absence of such challenges? Obviously he would have just rolled over in bed and gone back to sleep. So by snoring his life away in luxury and comfort he never would have developed into the mighty Hercules.”

Epictetus

You’re probably thinking: fulfilling the needs on the hierarchy is important and it’s a noble goal. Sure, but where do we draw the line? I would argue that it’s only when we take for granted the needs on the lower levels, that we feel the need to strive for more.

Another thing I’ve noticed is that we jumble up the hierarchy so that status or self-esteem for instance are treated as more important than our health or employment. This is what happens when we take everything for granted, we develop a habit of choosing the easier paths.

Look around you. Look at the consequences of a society that rewards that type of behaviour. We have an obsession with easy credit. Canadians’ household debt levels are now at 177% of disposable income. That means we owe $1.77 for every dollar of household disposable income! 30 years ago, that figure was $.090.

How about the fact that worldwide obesity has tripled since 1975. And instead of working on losing weight and being healthy, we spend our time at the top of the hierarchy, working on self-esteem issues and pushing the body positivity movement.

Our society is like a helicopter parent, hovering around us to make sure we don’t get hurt.

But the thing is, is that we need to get hurt. Like Dumas said: “We must have felt what it is to die, that we may appreciate the enjoyments of life.”

“Constant misfortune brings this one blessing: those whom it always assails, it eventually fortifies.”

Seneca

Seneca’s idea seems to linger among the wisest individuals throughout history.

The research I had done for my previous post, “Race and Politics in African American Literature,” led me to the discovery of one such individual.

I recently finished reading his autobiography called Up From Slavery. It tells of his journey from a young slave; to the principle and educator of the Tuskegee institute in Alabama; to his address at the Atlanta Exposition that garnered him national celebrity status as a great leader and orator.

I am of course speaking of the African American leader, Booker T. Washington. And as I read his book, I found myself becoming captivated by his admirable, patient, generous, and impressively stoic character. This is from Up From Slavery:

“In later years, I confess that I do not envy the white boy as I once did. I have learned that success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has overcome while trying to succeed. Looked at from this standpoint, I almost reach the conclusion that often the Negro boy’s birth and connection with an unpopular race is an advantage, so far as real life is concerned. With few exceptions, the Negro youth must work harder and must perform his task even better than a white youth in order to secure recognition. But out of the hard and unusual struggle through which he is compelled to pass, he gets a strength, a confidence, that one misses whose pathway is comparatively smooth by reason of birth and race.”

That might be a controversial view, but think about what an attitude like that is capable of? He believed in the power of the individual. He was able to teach his students to harness and appreciate the advantage of character that misfortune hides beneath its thorns.

Washington’s philosophy was that merit, through labour, dedication, hard work, and usefulness, will reap rewards for anyone who chooses to demonstrate them, regardless of skin colour.

“The individual who can do something that the world wants done will, in the end, make his way regardless of race”

Booker t. Washington

Washington was motivated by a deep sense of generosity. He believed that the happiest of people were those who spent their time helping others. He was able to do the things he did in his life because he was able to let go of any feelings of resentment or anger.

Think of the activists now who are obsessed with our current social justice movements. Most of them are far too angry and resentful to create fundamental change. It’s important to remember that who we are, manifests itself into what we do. So if someone is full of negative energy; hell bent on destruction and revolution, they will re-create the same flawed system that they claim to tear down.

Even if by some miracle these people were given exactly what they wanted, can we realistically expect their characters to change too? They will still be the same ungrateful people that had taken advantage of the lower levels of the hierarchy, only now they will have been given another step on the pyramid to take for granted.

I’m reminded of a quote I saw recently.

“Only the guy who isn’t rowing has time to rock the boat.”

Jean-Paul Sartre

But what might happen if these people practiced gratitude instead? Would they still be fighting for surfing’s diversity problem? Or would they be happy that they live in a country where their oceans aren’t so polluted as to prevent them from partaking in the activity in the first place?

What if we all took some much needed advice from one of the greatest leaders of all time?

When you arise in the morning, think of what a precious privilege it is to be alive – to breathe, to think, to enjoy, to love.

Marcus Aurelius

I want to be clear, I’m not saying that some change doesn’t need to happen. I’m only saying that positive change is more likely to come from a place of love and acceptance as opposed to force, bitterness, and resentment. This is from Washington again:

“I early learned that it is a hard matter to convert an individual by abusing him, and that this is more often accomplished by giving credit for all the praiseworthy actions performed than by calling attention alone to all the evil done”

In order to find these praiseworthy actions, we need to have an eye for gratitude. I encourage you to think about the concept of gratitude for a while. Meditate on it, put its meaning in every conceivable context you can imagine and realize its potential. If you do, I promise that you’ll learn that:

“Gratitude is not only the greatest of the virtues, but the parent of all of the others.”

Cicero

When you feel genuinely grateful for your position in life, whatever it may be, you’ll find that there isn’t any room to take things for granted.

The path to happiness isn’t about moving higher on Maslow’s hierarchy, it lies in the appreciation of the foundations on which you are able to climb.

“Do not spoil what you have by desiring what you have not; remember that what you now have was once among the things you only hoped for.”

Epicurus

We also need to understand that we don’t need to live in a world where misery and misfortune are removed. We need to learn to be grateful for them, despite how much they might hurt. We need to appreciate pain, and we need to understand that adversity builds character and that avoiding uncomfortable situations will only make us ungrateful and weak.

“The way to paradise is an uphill climb whereas hell is downhill. Hence, there is a struggle to get to paradise and not to hell.”

Al-Ghazali

“Amor Fati’ is a latin phrase and Stoic principle that I find helpful. It means to “love one’s fate.” Even if you find that your fate is plagued with difficulty, realize that you have a choice. You can choose to become a victim, and expect the world to change for you, or you can be grateful, to appreciate the opportunity you were given to strengthen your character. What’s not to love?

And as usual, here’s some more Emerson.

“Cultivate the habit of being grateful for every good thing that comes to you, and to give thanks continuously. And because all things have contributed to your advancement, you should include all things in your gratitude.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Thanks for reading.

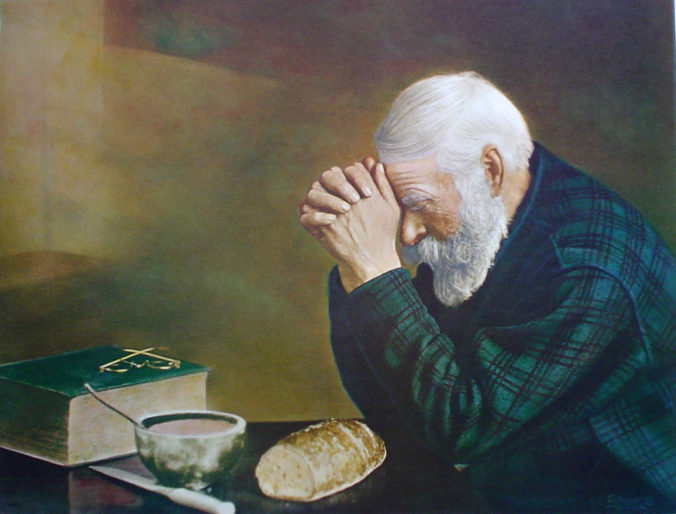

Featured Image: “Grace” by Eric Enstrom

Recent Comments