“This is a book about wisdom,” is the very first line of The Coddling Of The American Mind, How Good Intentions And Bad Ideas Are Setting Up A Generation For Failure by social psychologist, Jonathan Haidt, and attorney, Greg Lukianoff

The book is a deep dive into some contemporary shifts of university campus culture over the past decade, and it attempts to explain, from a predominantly psychological perspective, the presence of three great “untruths” that are behind these shifts in trends and behaviours.

The great “untruths” are:

- The Untruth of Fragility: What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker.

- The Untruth of Emotional Reasoning: Always trust your feelings.

- The Untruth of Us Vs Them: Life is a battle between good people and evil people.

According to Greg and Jon, these are called “untruths” because they meet three criteria: they have to contradict ancient wisdom, they have to contradict modern psychological research and well being, and they have to harm the individuals and communities that embrace them.

And although The Coddling is specifically aimed at dissecting the small subculture of upper-middle class university students born 1995 and later, I think the issues it raises can be applied much more broadly.

I think it’s through the lens of these untruths that we can better understand the social justice movement that is defining our current cultural zeitgeist, as well as the political divide that seems to be widening at an increasingly alarming rate.

I’ve spent the last few months reading several non-fiction books regarding these general topics, which will hopefully allow me to paint a more encompassing picture of the whole.

I’ll also attempt to highlight some of the more troubling aspects and potential consequences of one movement in particular by exploring some concepts and ideas that are imbedded in it’s aims.

I apologize ahead of time for the length. The truth is, I’ve been thinking about these ideas for the past 6 months or so, and I’ve been incredibly reluctant to write about them. But as time went by, I noticed I was just accumulating information that I wanted to include and was faced with the monumental task of trying to parse through it all and put it together in a cohesive manner. I’m not sure I accomplished that, but I got a lot off my chest and it feels good to be done.

I hope you get something out of it.

The Untruth of Fragility: What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker.

I’ve written about the antithesis of this untruth before; the ideas that what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger, and that we actually benefit from shouldering adversity instead of avoiding it. The Stoics are known for this type of thinking. But as opposed to merely reciting quotes from the ancients, The Coddling gives numerous real world examples of what happens when there is an absence of this time-tested principle.

To help illustrate their point, they use one example that I’m sure everyone has heard about, or even had to deal with in the last few decades: the rise of peanut allergies in children.

The authors show how school administrators and parents – with the good intention of protecting children from harm – have actually made the problem much worse over the years.

According to one survey, peanut allergies were rare prior to the 1990’s, affecting about four out of a thousand children. When the same survey was done again in 2008, the rate had roughly tripled to fourteen out of a thousand.

In 2015, a study called LEAP, or Learning Early About Peanut Allergies, found some surprising results.

640 infants (aged four to eleven months), who were a high risk for developing allergies, were split into two groups. The first group’s parents were told to follow the standard advice, that is, avoiding exposure to peanuts; while the second group’s parents were given a supply of a snacks that contained peanut butter, and were told to give it to their children three times a week.

“Among the children who had been “protected” from peanuts, 17% had developed a peanut allergy. In the group that had been deliberately exposed to peanut products, only 3% had developed an allergy. Peanut allergies were surging precisely because parents and teachers were trying to protect children from them.”

That’s because the human body needs exposure to foods and bacteria in order to develop an immune response to them. We are what the author and polymath Nassem Nicolas Taleb would call Antifragile.

In his book of the same name, Taleb categorized three types of things: things that are fragile, that can break easily and cannot heal themselves; things that are resilient, that can withstand shocks but do not benefit from such shocks; and finally, things that are antifragile, meaning, things that require stressors, shocks, and challenges, which are needed for them to grow, adapt, and learn.

Antifagile things include some of our political and economic systems, our immune systems, and our muscular systems.

Taleb provides us with an image to help with his idea: wind can extinguish a candle, but it can also energize a fire. He encourages us not to turn our children into candles, but rather: “to be a fire and wish for the wind.”

And there is no shortage of wisdom that corroborates this idea.

“Let me embrace thee, sour adversity, for wise men say it is the wisest course.” -Shakespeare

“Difficulties strengthen the mind, as labor does the body.” – Seneca

“The wound is the place where the light enters you.” – Rumi

“He who sweats more in training bleeds less in war.” – Greek Proverb

“A gem is not polished without rubbing, nor a person perfected without trials.” – Chinese Proverb

“Prepare the child for the path, not the path for the child.” – Thomas P. Johnson

But despite all that, it still seems like our society is doing exactly the opposite.

Helicopter parenting, safe-spaces, microagressions, call-out culture, trigger warnings; these are just a few of the recent ideas to emerge that are based on the assumption that we are fragile and need to be protected.

Greg and Jon show that despite the good intentions of protecting people from emotional or psychological harm, these ideas are having unintended negative consequences on our social, emotional, and intellectual development and well being.

The Untruth of Emotional Reasoning: Always trust your feelings.

To help discuss the second untruth and how it relates to the first, Greg and Jon break down something called “concept creep.”

To explain this idea they cite the influential paper: “Concept Creep: Psychology’s Expanding Concepts of Harm and Pathology” by Nick Haslam.

They use the example of “trauma” in the book and show how its definition has changed over time. (Other concepts that also apply include bullying, prejudice, abuse, and addiction.)

They note that in the first editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or the DSM, “trauma” was used only to describe physical damage or injury. But in the 1980’s, in the DSM-3, post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, became recognized as a mental disorder.

However, at that time, the criteria for a diagnosis was still measurably objective. To qualify, an event would have to “evoke significant symptoms of distress in almost everyone” and be “outside the range of usual human experience,” with things like war, rape, or torture, for example.

But in the 2000’s, the concept began to slide into subjective territory. “Trauma” now meant “anything experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful… with lasting effects on the individuals’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”

This meant that anything from a break-up to the a death of a loved one could be considered traumatic. It evolved into an individuals perceptions of an experience that defined whether or not trauma had occurred.

This shift in diagnostic criteria, from objective to subjective, poses a problem for the authors, because they know that we, as humans, are often terrible at assessing our own feelings.

That’s because many of the feelings we have are influenced by what are called cognitive distortions. They include:

- Emotional reasoning: Letting your feelings guide your interpretation of reality. “I feel depressed; therefore, my marriage is not working out.”

- Catastrophizing: Focusing on the worst possible outcome and seeing it as most likely. “It would be terrible if I failed.”

- Overgeneralizing: Perceiving a global pattern of negatives based on a single incident. “This generally happens to me. I seem to fail at a lot of things.”

- Dichotomous thinking (also known as “black-and-white thinking,” “all-or-nothing thinking,” and “binary thinking”): Viewing events or people in all-or-nothing terms. “I get rejected by everyone,” or “It was a complete waste of time.”

- Labeling: Assigning global negative traits to yourself or others (often in the service of dichotomous thinking). “I’m undesirable,” or “He’s a rotten person.”

- Mind reading: Assuming that you know what people think without having sufficient evidence of their thoughts. “He thinks I’m a loser.”

- Negative filtering: Focusing almost exclusively on the negatives and seldom noticing the positives. “Look at all the people who don’t like me.”

- Discounting positives: Claiming that the positive things you or others do are trivial, so that you can maintain a negative judgment. “That’s what wives are supposed to do – so it doesn’t count when she’s nice to me,” or “The successes were easy, so they don’t matter.”

The “cure” for this type of thinking is called cognitive behavioural therapy, or CBT, and it has proved to be an effective method of treating mental disorders by helping us become aware of these negative thoughts and thought patterns. In many studies, CBT has been demonstrated to be as effective as, or more effective than, other forms of psychological therapy or psychiatric medications. 23

It’s like a modern form of Stoic philosophy.

“What really frightens and dismays us is not external events themselves, but the way in which we think about them. It is not things that disturb us, but our interpretation of their significance.”

Epictetus

Another issue that makes our subjective judgments notoriously unreliable is our common use of logical fallacies. Whether we deliberately use them or not, fallacies are deceptive or unsound arguments that we may use to justify certain behaviours and decisions we make.

A few common examples include: rejecting an idea based on the person supporting it, as opposed to the idea itself. (Ad Hominem); believing that something is wrong, for example, because it is against the law, and assuming it must be against the law because it is wrong (circular reasoning); drawing conclusions based on too small of a sample size (hasty generalization); a greater tendency to continue an endeavour once an investment in money, effort, or time has been made (sunk cost fallacy); the erroneous thinking that a certain event is more or less likely, given a previous series of events (gambler’s fallacy); a form of argument in which the opinion of an authority on a topic is used as evidence to support an argument (appeal to authority); claiming a proposition is true because a significant amount of people believe it (bandwagon fallacy); and an attempt to protect a universal generalization from a falsifying counterexample by excluding the counterexample improperly (no true Scotsman fallacy). We will encounter this last one shortly.

There are many more, and they are more common than you might think. If you really pay attention, you’ll start to notice them everywhere.

Unfortunately, if everyone had a healthy skepticism regarding their own reasoning capabilities, feelings, and emotions, Greg and Jon wouldn’t have felt compelled to write a book about the pitfalls of always trusting them.

On the other hand, it’s also not healthy to completely disregard our emotions and feelings when assessing situations either.

The point is that we should strengthen them, and because we are antifragile, we need to challenge them sometimes, and not always take them as truth.

That is the great fallacy: the wisdom of old men. They do not grow wise. They grow careful.”

Ernest Hemingway

The Untruth of Us Vs Them: Life is a battle between good people and evil people.

To help explain this last untruth I need to explain a few complicated ideas, so bear with me.

In Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay’s book, Cynical Theories, they trace the lineage of Postmodern philosophy to its roots and identify some underlying principles of postmodernism that are driving the social justice movements like Critical Race Theory, Post-colonial Theory, Gender and Queer Theory, and Fat and Disability studies.

They explain that these critical theories are connected to two fundamental principles that were first developed by two french philosophers in the 1970’s: Michel Foucault and Jaques Derrida. The former, according to google scholar, has been cited 1,248,139 times in academic papers (468,931 times since 2016 alone), which gives you an idea of the scale and velocity of these movements. 4

Their ideas are: the postmodern political principle, which holds that “the social construction of knowledge is intimately tied to power, and that the more powerful culture creates the discourses that are granted legitimacy, and determines what we consider to be truth and knowledge.”

And the postmodern knowledge principle, which “rejects whether objective knowledge can be obtained” and assumes that “knowledge is a socially constructed cultural artifact.”

Right away we can see how these ideas relate to the second untruth; as the Critical Race Theorist Charles R. Lawrence writes in “The Word and The River”:

“We must free ourselves from the mystification produced by the ideology of objective truth, we must learn to trust our own senses, feelings, and experiences, and to give them authority, even (or especially) in the face of dominant accounts of social reality that claim universality.”

Since they reject the idea of objective truth, many of the critical theorists who cite these philosophers also reject the idea of “value free” knowledge. Which means that the knowledge that a given researcher might have discovered using the scientific method or reasoned debate, for instance, will always be tainted by the researcher’s identity, biases, emotions, and values, and should therefore, not be considered more valuable than other ways of knowing.

Many of these ideas are rooted in the Marxian conception that all human behaviour can be explained as the struggle for power between groups. Karl Marx applied these ideas to criticize capitalism by arguing that the class struggle between the proletariat and bourgeoisie would inevitably lead to a revolution of the working class, who would develop “class consciousness,” and establish a communist utopia.

Today, scholars apply Marx’s conflict theories to explain power dynamics within other forms of identity as opposed to just class differences.

Which brings us to something called standpoint theory, or standpoint epistemology (Epimitomology meaning the study of knowledge). It’s an idea rooted in the postmodern political and knowledge principles which claims that people within the same identity group, like race, sex, or gender, for example, will have the same experience as others within the same group, (assuming they are authentic) and that their place in a given power dynamic (intersectionality) dictates what one can or can not know.

Thankfully, Pluckrose and Lindsay explain it simpler terms:

“Standpoint theory can be understood by analogy to a kid of colour blindness, in which the more privileged a person is, the fewer colours she can see. A straight white male – being triply dominant – might thus see only in shades of grey. A black person would be able to see shades of red; a woman would be able to see shades of green; and a LGBT person could see shades of blue; a black lesbian could see all three colours – in addition to the greyscale vision everyone has.”

The idea of intersectionality was first developed by the legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, who used it to point out racial and gender discrimination in company hiring practices. The idea was that a business, for example, could make an effort to hire more black people and more women, and they could hire more black men and more white women to meet their goal, but ignore black women in the process.

I don’t deny that there are useful ideas in critical theory, and I must admit that I am little aquatinted with the actual philosophy beyond a surface level understanding. But that’s not to say that what has emerged from these theories and ideas requires a deep understanding of them in order to see how some of their interpretations are unwise, and are likely to do more harm than good.

When referring to the same subject in The Coddling, Greg and Jon state explicitly that:

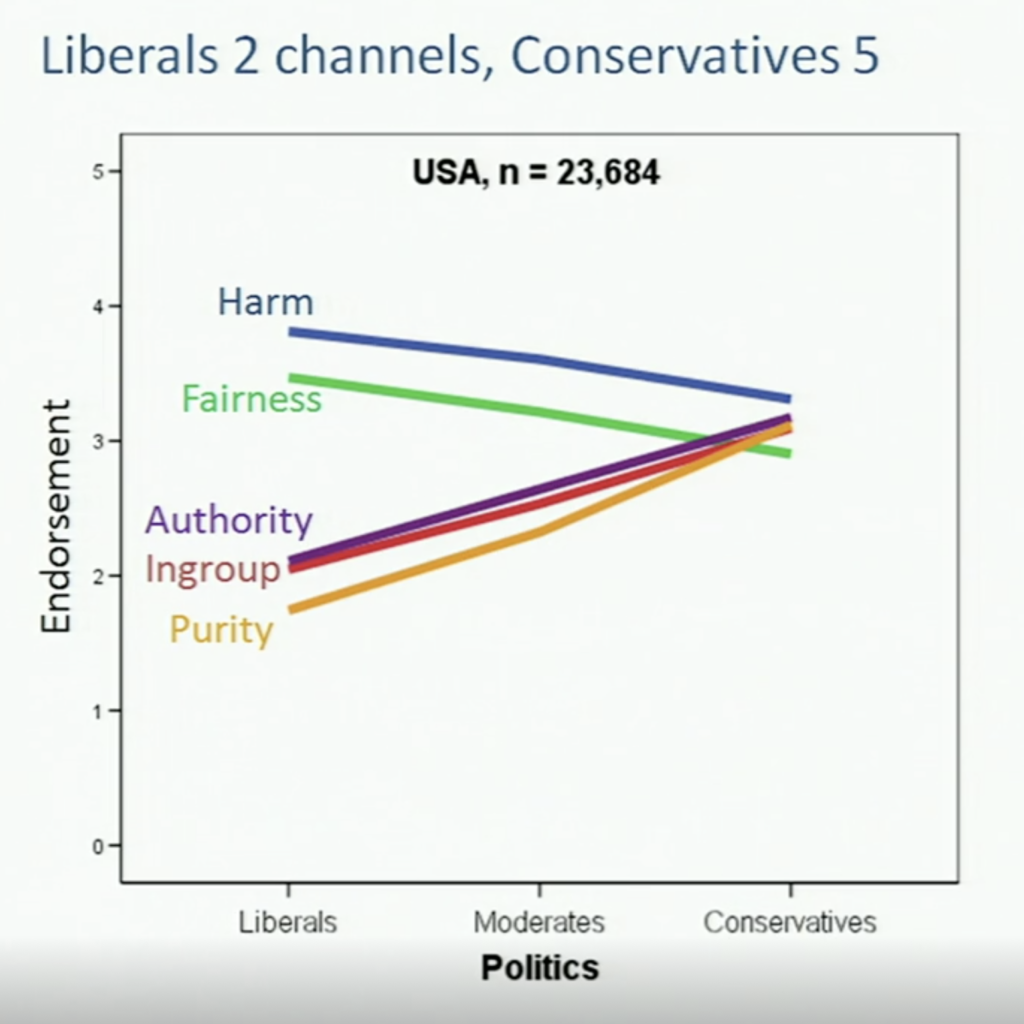

“Our purpose here is not to critique the theory itself. It is, rather, to explore the effects that certain interpretations of intersectionality may now be having on college campuses. The human mind is prepared for tribalism, and these interpretations of intersectionality have the potential to turn tribalism way up. These interpretations of intersectionality teach people to see bipolar dimensions of privilege and oppression as ubiquitous in social interactions…”

They provide a helpful tool for understanding standpoint epistemology and intersectionality.

/media/img/posts/2018/10/axis/original.png)

They continue:

“Since “privilege” is defined as the “power to dominate” and to cause “oppression,” these axes are inherently moral dimensions. The people on top are bad, and the people below the line are good. This sort of teaching seems likely to encode the Untruth of Us Versus Them directly into students’ cognitive schemas: Life is a battle between good people and evil people.”

The Three Untruths and Critical Theory In Practice

One of the theories to emerge from postmodernism and critical theory is something called Critical Race Theory, or CRT.

It’s defined here by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic in their book Critical Race Theory: An Introduction:

“The critical race theory (CRT) movement is a collection of activists and scholars interested in studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power. The movement considers many of the same issues that conventional civil rights and ethnic studies discourses take up, but places them in a broader perspective that includes economics, history, context, group- and self-interest, and even feelings and the unconscious. Unlike traditional civil rights, which stresses incrementalism and step-by-step progress, critical race theory questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law.”

On the surface, it sounds pretty harmless, except the last part, but I’ll get to that later.

What CRT actually looks like, is something that Pluckrose and Lindsay write about in Cynical Theories:

“…it puts social significance back into racial categories and inflames racism, tends to be purely theoretical, uses the postmodern knowledge and political principles, is profoundly aggressive, asserts its relevance to all aspects of social justice, and – not least – begins from the assumption that racism is both ordinary and permanent, everywhere and always.”

It should be mentioned that CRT in the purely academic sense is just that, a theory, and it undoubtedly belongs in the market place of ideas, but to reiterate, some of the interpretations, the practices, and the rhetoric that are emerging from its teachings can be incredibly destructive and disempowering.

Broadly speaking, some of the major claims CRT makes is that America is an irredeemably racist country, and that racism is embedded in the very fabric of society. It also claims that “racism is codified in law, embedded in structures, and woven into public policy, while rejecting any “claims of meritocracy or “colourblindness.” “17

Additionally, CRT scholars insist that all white people are racist, are inherently privileged, and are all given the moral status of oppressor.

The scholar and activists Robin DiAngelo, summarized her interpretation of CRT in one of her speaking events by declaring: “The question is not ‘Did racism take place?’ but rather ‘How did racism manifest in that situation?'”

And to help answer her question, the author of the New York Times best seller, White Fragility, composed a list of “Common White Patterns that obscure and protect racism,” which included, among others, “a focus on intentions over impact”, “defensiveness about any suggestion that we are connected to racism,” and “seeing ourselves as individuals outside of racial socialization.”3

This contains some alarming messages, first, she’s arguing that denial or pushback is proof of racism, second, she’s rejecting individuality in favour of a form of collectivism based on some immutable characteristics, and third, she’s teaching the great untruth of always trusting our feelings by explicitly stating in the same document that “intentions are irrelevant.”

Apply the last claim to the idea of microagressions, for example, which are defined as statements, actions, or incidents regarded as instances of indirect, subtle, or unintentional discrimination.

Some common examples of microaggressions include saying: “I’m colourblind, I don’t see race,” “All lives matter,” “I believe the most qualified person should get the job,” or “I’m not a racist. I have several Black friends.” Even the concept of personal responsibility, or just being a white person who waits to ride the next elevator when a person of colour is on it are considered offensive.6

Microaggressions, much like how we diagnose trauma today, work by assuming if you feel offended, or marginalized, or a victim of prejudice, then therefore, it must be true.

Except the problem is, what if that particular person of colour on that elevator was your friends talkative ex girlfriend? Or she smelled bad? Or was eating spaghetti with too much parmesan cheese?

There could be a million reasons of not getting on the elevator that aren’t racially motivated, and thinking that way is both dangerous and unhelpful.

Instead of training oneself not to interpret the world by catastrophizing or mind-reading, as Greg and Jon point out, DiAngelo is encouraging people take the least generous view of events, and to constantly view others with a sense of hostility and paranoia.

Wisdom tells us that behaviour like this will not lead to charitable, well-educated, confident, and open-minded people.

Furthermore, if saying “The most qualified person should get the job,” could somehow be misconstrued as meaning that people of colour are generally not as intelligent as whites, CRT is guilty of its own logic by attributing (I would argue) objectively positive things to “Aspects and Assumptions of White Culture,” in the infamous infographic by the Smithsonian Museum. 15

Among the list were rugged individualism, self-reliance, family structure, emphasis on the scientific method, protestant work-ethic, justice, competition, planning for the future, delay of gratification, and the following of rigid time schedules.

Like Greg and Jon have stated, because we have placed racial identities on a moral axis of privilege and oppression, these examples are both harmful to the people of colour who have been told that these things aren’t a part of their culture, as well as implying that they are oppressive if you’re white. It’s condescending and divisive.

I found a few posts on Twitter that will give you an idea of the type of language and behaviour that is being influenced by some of these ideas.

And this stuff is happening in high-schools and corporate settings too.

A Las Vegas high-school student named William Clark “received a failing grade in a critical race theory course after he refused “to publicly reveal his race, gender, religious and sexual identities” and “to confess his white dominance.”16

Even in Canada, the new grade 9 math curriculum in Ontario has been changed to address the issue that: “Mathematics has been used to normalize racism and marginalization of non-Eurocentric mathematical knowledges.” 19

Similarly, in a well-intentioned racial sensitivity training session at Coca Cola, employees were explicitly told to “Be less White.” 18

And these aren’t rare occurrences either, Christoher Rufo, a filmmaker turned CRT critic, has collected hundreds of such examples throughout Canada and the United States. His work ignited widespread support from conservatives after he called on Donald Trump to ban Critical Race Theory from schools, which he did (something I don’t agree with). This inevitably led to responses from left wing media outlets criticizing the political right of not being on the side of social justice, and of opposing it’s central of tenets of diversity, inclusivity, and equity, among the typical accusations of racism.

But rather than talk about the political ramifications of critical race theory here, I want to stick to the psychological consequences of the CRT’s rhetoric for now.

In her open letter titled, “Why Im leaving the Cult of Wokeness,” Africa Brooke writes:

“... for ME, (this language) does nothing but give me false reminders of my supposed oppression…which rubs me the wrong way entirely because I AM NOT OPPRESSED. I think it’s key that we begin to accept that black people don’t all share a singular experience, nor do we share the same brain.” 23

In response to CRT, a student at the University of Alabama remarked, “As a black college student, I’m certainly not paying to sit in a classroom and be told that I’m a helpless victim – that regardless of how hard I try, or how hard I work, it’ll never be enough because racism will always win.” 20

Another name for this is called the soft bigotry of low expectations, and it relates to a psychological concept Greg and Jon discuss in The Coddling called “locus of control.”

They explain that that people can be trained to either have an internal locus of control, or an external locus of control. An internal locus of control means that people have learned to expect that they could get what they wanted through their own behaviour. On the other hand, an external locus of control means that people have learned to believe that nothing they did mattered.

According to Greg and Jon, “a great deal of research shows that people with an Internal locus of control leads to greater health, happiness, effort expended, success in school, and success at work.”

Instead, CRT is teaching people the opposite, and the consequences of which could be directly harming the very people it’s meant to be helping.

However, as we saw earlier, not everyone is as reluctant to accept the victim label.

In Bradley Cambell’s and Jason Manning’s book, The Rise of Victimhood Culture: Microaggressions, Safe Spaces, and the New Culture Wars, they point out our society’s transition from dignity culture, and honour culture, to a one of victimhood, where being a victim comes with its own “natural moral currency.” Victimhood offers a sort of status, one that generates sympathy, and gives the victim support from third parties, and also “increases the incentive to publicize grievances “

The attention and sympathy that victimhood provides is so desirable for some, that there have even been a number of hoaxes perpetrated in order to gain victim status for personal gain.

In Gad Saad’s book, The Parasitic Mind, he calls this phenomenon of feigning victimhood: Collective Munchausen Syndrome (CMS). The name comes from the mental disorder called Munchausen syndrome, where a person feigns an illness in order to get sympathetic attention from a caregiver.

One of the most famous examples of CMS is the story of the Empire actor Jussie Smollet. As Saad writes, “(he) was unhappy with his “meagre” salary (more than $1 million per year)”, and was “undoubtedly displeased with his lack of fame” so he paid two Nigerian-Americans to orchestrate a hate crime on himself in order “to ascend the victimhood hierarchy.” He told police that the two attackers wore MAGA hats and used racial slurs, poured an unknown substance on him, and put a noose around his neck.

Smollett was eventually charged for filing a false police report and came to an agreement to do community service and to forfeit his $10,000 bond. Later, the city of Chicago filed a lawsuit against him claiming the investigation of the alleged attack cost them over $130,000. He then countersued, saying he was a victim of “mass public ridicule and harm.”

The journalist and professor of political science Wilfred Reilly wrote an entire book about events like these called Hate Crime Hoax: How the Left is Selling a Fake Race War. He documents hundreds of such incidents that have happened over the last five years.

If people are willing to go to such extreme lengths to be a victim, it’s no wonder why the combination of always viewing life through the lens of racial identity, constantly being encouraged to be on the alert for microagressions, and placing oneself on the binary of oppressor vs oppressed, might be potentially harmful, and could actually do more to inflame racism rather than overcome it.

You might be thinking: “well, none of this really affects me, I know I’m not a victim, or, I know I’m not racist.” But Ibram X. Kendi, the author of the book, How To Be An Antiracist, goes even further and says that if your aren’t actively fighting against racism, then you are in fact, a racist. “I don’t think people realize that when they self-identify as ‘not racist’, they’re essentially identifying in the same way as white supremacists…”2

He makes the additional assertion that: “The only remedy for racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy for present discrimination is future discrimination.” And declares: “When I see racial disparities, I see racism.”

If that’s not alarming enough, the New York Times called his book, How to Be an Antiracist, “the most courageous book to date on the problem of race in the Western mind.”

The economist Thomas Sowell, in his book, Economic Facts and Fallacies, when referring to racial disparities, points out the potential harmful effects of Kendi’s ideas:

“To say that some people have less probability of achieving a given income or occupational level is too often automatically equated with saying that society puts barriers in there path. This precludes ‘a priori’ the very possibility that their might be internal reasons for not doing well economically as other people. Moreover, this is not just a matter of abstract judgment to the extent that there may in fact be internal reasons for not achieving as much as others, directing attention away from those reasons has the practical effect of reducing the likelihood that those reasons will be addressed and the potential for advancement improved. In short, those who are lagging are offered a better public image, instead of better prospects.“

Systemic Racism?

DiAngelo’s and Kendi’s rise to fame, and the popularity of Critical Race Theory in general, was undoubtedly galvanized by the murder of George Floyd last year, and the massive protests that erupted in response.

Racially motivated police brutality became under close scrutiny and a narrative was pushed by the mainstream media which produced some surprising results.

In his article titled, “The Good News They Won’t Tell You About Race in America,” Reilly writes:

“Skeptic Research Center found that 31 percent of individuals who identify politically as very liberal believe that “about 1,000” unarmed black men were killed by police just during 2019, and another 14 percent believe that “about 10,000” such men were killed. Conservatives did a bit better, but, among ordinary mainstream liberals, the equivalent figures were 27 percent and almost 7 percent.”

The real number was 13.

But even 13 is too much. And the overwhelming consensus was that these killings were racially motivated. In an interview with the writer and podcast host Coleman Hughs, Reilly points out why that is.

In the U.S., about 14 percent of the population is black, and 23 percent of the police killings were black, therefore, one might conclude, the 9 percent representative difference would be proof of racial bias. The problem is that that’s assuming that the police encountered individuals of the different races at the same relative rate, which is not true. To put it in perspective, the most common age of white people in the U.S. is 58, and is 27 for blacks. So it’s not so surprising to expect more black encounters with police given the correlation between age and crime. Another possible correlation could be attributed to differences in class, which also has a major correlation to crime, and also to age, neither of which are issues of racial bias. And when these statistics are adjusted to take in the rates of encounters, the disparity vanishes. 7

The economist Roland Fryer wrote a paper in 2016 that supported these conclusions.

The Writer and cultural/political commentator Leonydus Johnson posted the same argument on his Twitter feed, Here.

Another journalist wrote about it Here.

Hughs made an alternative argument on his podcast suggesting it was George Floyd’s killing that became the fuel for a sort of proxy by which marginalized groups were able to express frustration against lesser forms of non-violent racial bias. Which would no doubt have been inflamed by the rise of the social justice movements and the divisive rhetoric of CRT.

Elsewhere, in his article titled, “The Racism Treadmill,” Hughs cites another example of how mainstream media commonly commits the fallacy of attributing disparities to discrimination:

…a recent study by researchers at Stanford, Harvard, and the Census Bureau found that, “[a]mong those who grow up in families with comparable incomes, black men grow up to earn substantially less than the white men.” A New York Times article attributed this disparity to “the punishing reach of racism for black boys.” But the study also found that black women have higher college attendance rates than white men, and higher incomes than white women, conditional on parental income. The fact that black women outperformed their white counterparts on these measures, however, was not attributed to the punishing reach of racism against whites.“

The linguist John McWhorter had this to say about the idea of “systemic racism” while discussing the disparities present in test scores on Glen Loury’s podcast at bloggingheads.tv:

“It’s unusual to say the reason that these kids aren’t doing well on the test is not something that can be gracefully called racism, maybe it’s traceable to something racist in the past, but we live in the present. So that’s what worries me about the term, because it always implies that that animus you have against bigotry is the same feeling you should have when black people aren’t as good as something as white people for some reason. You’re supposed to have your lower lip poked out and your supposed to have that same feeling that ‘it’s racism’. But usually that’s a simplistic solution that doesn’t end up helping anybody. It’s a very elementary way of looking at how human beings operate in time and space. So the term makes me uncomfortable. If somebody says ‘is there systemic racism?’ and they mean ‘are there these inequities?’ Yes. ‘Are these inequities due to racism in the past?’ Yes. ‘By the past do I mean only in black and white in 1914?’ No. I know about redlining, and it goes even beyond that. But is the solution to problems due to this thing were calling ‘systemic racism’ to undue the racism?… it seems to me that that leads us down some paths that no civil rights leader, even 50 years ago, would have seen any sense in. It is my least favourite expression in the english language at this point. It’s distracting.” 14

The truth is, neither Reilly, Hughs, Johnson, Sowell, Loury, or McWhorter would deny that racism exists, or that it’s a problem, but they all seem to agree that it’s not reached the alarming proportion of “systemic.”

And neither would they agree that they way to end racism is through divisive ideas like Critical Race Theory. McWhorter even wrote a piece in the Atlantic about Robin DiAngelo’s book, titled, “The Dehumanizing Condescension of White Fragility.”

But Critical Race theorists have an answer for opposing viewpoints coming from black intellectuals like these: according to standpoint epistemology, they would not be considered authentically black, rather, they would have just internalized their racism. (Remember the “no true Scotsman fallacy”?)

Their argument is basically one of race essentialism, or in other words, racist. And it’s usually accompanied by the typical accusations of “sellout” or “uncle tom.”

That’s just one of the ways in which Critical Race Theory is unfalsifiable.

It’s like a conspiracy theory. If a white person criticizes it, it can be disregarded as evidence of racism with the claim that a white person is only attempting to uphold “white supremacy”; if a black person criticizes it, it can be disregarded by saying that they have just been socialized by the “white” dominant discourses.

Another aspect that makes it difficult to criticize is that, in doing so, it’s assumed that its detractors are against the teaching of black history (this is the most common defense). They are purposely conflating the two ideas as if they were synonymous. Which is completely untrue. Kimberlé Crenshaw, the founder of Critical Race Theory, is even on record saying that the term “Critical Race Theory” can be “used as interchangeably for race scholarship as Kleenex is used for tissue”

They are using the fallacy of false equivalence. Here is a perfect example from Reuters:

“The poll showed that a bipartisan majority of Americans say that high school students should learn about slavery and racism in America. Yet respondents were more opposed to teaching critical race theory, which maintains that the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow racial segregation laws continues to create an uneven playing field for nonwhite Americans.” 24

They didn’t bother to explain how, or why, or even bother mentioning that perhaps it’s because they are not the same thing.

But, an important criticism, just like how the peanut allergy backfired for the well-intentioned parents and teachers looking to prevent peanut allergies, is that, according to Cynical Theories, certain interpretations of CRT could be unintentionally “undermining antiracism activism by creating skepticism and indignation and thus producing a reluctance to cooperate with worthwhile initiatives to overcome racism.”

Like the indignation and skepticism that might arise from the blatant double standards present in this story:

During a lecture at the Yale University of Medicine, the psychiatrist, Dr. Aruna Khilanani said, “I had fantasies of unloading a revolver into the head of any white person that got in my way, burying their body, and wiping my bloody hands as I walked away relatively guiltless with a bounce in my step. Like I did the world a fucking favour,”

She also said that she stopped communicating with her white friends as “there are no good apples out there” because “white people make [her] blood boil.”

I’ll leave it up to the reader to imagine what kind of backlash might have ensued had an influential white person at a prominent university said that about any other race.

Backlash from criticizing Critical Race Theory

According to the Angus Reid Institute public opinion poll, 70% of Canadians said they self-censor to avoid offending others. 87% say they’re being polite when they self-censor, rather than trying to avoid judgement. And 80% say it “seems like you can’t say anything” without offending someone these days.”

Partly the reason why it took so long for me to write this post, and why I was so reluctant to do so, was because I’ve seen how people respond to criticisms of CRT, or even of racial discussions in general.

We live in a world where people can lose their jobs by making contentious observations,12 and where university campuses are censoring speech they find offensive or inappropriate.29 Even academics who write contentious papers are forced to redact them, and are ridiculed and shamed. 28

This fear of being on the wrong side of public opinion is a very real phenomenon that gives these social justice movements so much power.

I have a feeling that what’s happening is something that social psychologists call “pluralistic ignorance.” Put simply, it’s described as: “no one believes, but everyone thinks that everyone believes.” A common example of this is when young people drink in excess, even to the point of puking. Privately, most will admit that they don’t like the idea of heavy drinking, but since they believe everyone else enjoys it, and since they don’t want to show any signs of disapproval, they continue to do so. (see the story of “The Men Who Couldn’t Stop Clapping”.)

Because, by publicizing my disapproval of CRT, I have no doubt that if this post gained popularity I would be called any combination of bigot, racist, nazi, fascist, or white supremacist, despite not making any definitive or controversial declarations of my own. Name calling is one of the go to defences coming from the left. Or in other words, as Sowell likes to say, “arguments without arguments.”

Or as the author Christopher Hitchens calls it:

“…the pseudo-Left new style, whereby if your opponent thought he had identified your lowest possible motive, he was quite certain that he had isolated the only real one.”

Even while I was doing research for this post, I saw how many left-wing media sites who were covering CRT in the news were saying people like me were only trying to “stir up hysteria” in order to prevent “a fuller inclusion of more people and an expansion or rights.” 13

It’s gotten to the point now where political affiliation is more important than reasoned debate. They throw accusations like that as if to shepherd their readers away from engaging in the opposition’s ideas.

It seems to me, as Sowell once put it, “The problem isn’t that Johnny can’t read. The problem isn’t even that Johnny can’t think. The problem is that Johnny doesn’t know what thinking is; he confuses it with feeling.“

Because once more people on the left latch onto the idea of Critical Race Theory, and once more people on the right respond with attempts to ban it from schools and corporate training sessions, more people will support CRT simply because it signals that they are on the morally righteous political side, without having to do any thinking on their own.

That’s why these self-censorship statistics are so alarming to me; as well as why I don’t think the right should be banning CRT. Both are preventing necessary and thoughtful discussions about meaningful topics. If anything, I think CRT needs to be better understood so we can separate the wheat from the chaff.

But above all else, the claim that an idea like CRT cannot be criticized because of my skin colour is something that I’m willing to stand up against, and not only does that give me courage, it actually inspired me to put pen to paper in the first place.

Silencing opposing ideas, whether they’re contrary, offensive, or abrasive, especially if those ideas are coming from a good place, is wrong, no matter how you spin it.

We are not fragile. Being offended is not a bad thing. It’s a good thing. It allows us to strengthen our arguments, or maybe even see the merit in others. It allows us to grow, adapt, and learn, and to be more open-minded and charitable individuals.

As John Stuart Mill put it:

“The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.”

Collectivism vs Individualism

Remember the definition of CRT by Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic?

“…critical race theory questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law.”

In addition to the points I made earlier, I want to unpack this a little bit and make a few more arguments against CRT.

As opposed to the civil rights movements of the past that focused on the principle of individuality, shared humanity, and mutual respect, CRT centres around the principle of common enemies, and stresses the importance of collective group identity, as shown by DiAngelo’s claim that “seeing ourselves as individuals outside of racial socialization” is “a pattern of whiteness that obscures and protects racism.”

This push toward collectivism over individualism also relates to the general direction of CRT toward the advocation of centralized state power to implement the concept of equality of outcome as opposed to equality of opportunity, as suggested by Kendi’s assertion that “The only remedy for present discrimination is future discrimination.”

As Lindsay points out on his website, New Discourses, “Where equality means that citizen A and citizen B are treated equal”, equity means “adjusting shares in order to make citizens A and B equal.” – this is what the Critical Race Theorists mean when they aim to question equality theory.

For example, the CRT scholar Mari Matsuda believes that the victims of racism should be able to sue both the “perpetrator’s descendants and current beneficiaries of past injustice” for reparations.” Because all whites “continue to benefit from the wrongs of the past and… should be “taxed” for the sins of their race, even if they and their ancestors had nothing to do with racial oppression. 31

The problem with this however, according to Milton Friedman, and from what we learned from the atrocities of the 20th century by those who adopted Marxist ideologies, is that:

“A society that puts equality–in the sense of equality of outcome–ahead of freedom will end up with neither equality nor freedom. The use of force to achieve equality will destroy freedom, and the force, introduced for good purposes, will end up in the hands of people who use it to promote their own interests.

On the other hand, a society that puts freedom first will, as a happy by-product, end up with both greater freedom and greater equality.”

In The Gulag Archipelago, the famous Soviet dissident Alexander Solzhenitsyn lamented his countries fate, confessing that: “We didn’t love freedom enough. We purely and simply deserved everything that happened afterward.“

That’s because freedom is directly tied to individuality, as the writer John Pos Passos put it: “Individuality is freedom lived.”

Collectivism on the other hand, places a group’s priorities over those of the individual. And by subjugating the individual, groups can monopolize a sense of moral righteousness that favours the in-group, at the expense of the out-group. Taken to its logical extreme, collectivism will always end up treating the out-group poorly.

In predominantly collectivist cultures, people are more likely to be tied together by common ethical principles, share the same religion, and have the same goals, customs, and values. Unfortunately, in some countries this can translate to less individual rights for women, minorities, or even gay people, where homosexuality, for instance, can be punished by death.

Studies have revealed that even arbitrary distinctions between groups, such as preferences for certain paintings, or the colour of their shirts, can trigger a tendency to favour one’s own group at the expense of others, even when it means sacrificing in-group gain. 30

Additionally, the famous social experiment of the “Robbers cave study,” showed how quickly hostility can arise when groups are pitted against one another.

In contrast, individualists cultures tend to be more economically prosperous, which also tends to be correlated with their citizens enjoying more personal freedoms. In a study published by the APA, according to the meta-analysis of 63 countries, researchers “observed a very consistent and robust finding that societal values of individualism were the best predictors of well-being.” 32

The economist Friedrich Von Hayek once distinguished between the moral principles of individualism and collectivism: “That the ends justify the means in an individualistic perspective is the denial of all morals, but to a collectivist, it becomes the supreme rule.”

The reason why I’m making these points is because, as Lord Acton once said, “Liberty is not a means to a higher political end. It is itself the highest political end.“

And it’s this belief in individual liberty that helps define Liberalism in its classical sense of the word – Liberalism that is being attacked by proponents of CRT.

Classical Liberalism

Liberalism is a not an easy concept to explain in a few words, but some key tenets include: skepticism, the fallibility of man, that idea that subjectivity is a recipe for error, personal autonomy, an attempt to seek certainty, commitment to reason, the scientific method, universal human nature, and the psychological commonality that we are all reasoning beings.

Among the literal countless benefits to humanity that these ideas have endowed to us, Steven Pinker argues in his book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, that it was because of this humanitarian enlightenment that we “saw the first organized movements to abolish slavery, dueling, judicial torture, superstitious killing, sadistic punishment, and cruelty to animals, together with the first stirrings of systematic pacifism.”

It was the human capacity for reason that enabled us to see these things for what they were. Much of the unthinkable violence committed throughout human history can be summed up in this quote:

“Those who can make you believe absurdities, can make you commit atrocities.”

Voltaire

Pinker also points out that the progress made in the past of the rights of women, minorities, and gay people, have all been made possible by the ideas rooted in individuality and equality founded in humanitarian liberalism.

He concludes that these ideas have helped make the present day we live in right now the most peaceful in all of human history.

Furthermore, the neutral principles of constitutional law allowed justice to be distributed by rules, instead of rulers. We learned earlier about the dangers of subjective interpretations, which is why, for example, we’ve made the necessary distinction between manslaughter and murder; because intentions matter.

And objective truth matters.

Capitalism is another benefit made possible by liberalism that is frequently attacked by CRT.

As Kendi remarks: “The origins of racism cannot be separated from the origins of capitalism. The origins of capitalism cannot be separated from the origins of racism…In order to truly be antiracist, you also have to be anti-capitalist.”

What people like him seem to forget is that hundreds of millions of people have been raised out of poverty under capitalism in various countries around the world.

In 1820, 94% of the world’s population was living in extreme poverty. By 1910, this figure had fallen to 82%, and by 1950 the rate had dropped yet further, to 72%. However, the largest and fastest decline occurred between 1981 (44.3%) and 2015 (9.6%).26

Competitive free enterprise also enables and fosters incentives for work, saving, and investment. The common misunderstanding that capitalism is a zero-sum game – meaning that I can only do better while making someone else worse off – is demonstrably false. The old saying that the rising tide lifts all boats is an accurate descriptor. It’s a positive sum game – a two thank-you system; you say thank-you when you get your coffee, and the barista says thank-you for your payment.

So when these scholars say they are questioning the very foundations of liberal order by applying their postmodern political and knowledge principles, and concluding that these ideas are “white,” and that they uphold “white supremacy” just because they were written about and implemented by white men, it’s extremely concerning.

It’s concerning not only because attributing these ideas to one race might alienate others from viewing them as part of their own culture, as opposed to the whole human species, but the very ideas themselves, which contain the methods of criticizing other ideas using skepticism, reason, and science, are being viewed subjectively as unimportant, or racist in and of themselves.

For arguments sake, even if these things could be considered part of white culture, Sowell offers a poignant explanation of the dangers of rejecting them based on issues of cultural identity:

“If the dogmas of multiculturalism declare different cultures equally valid, and hence sacrosanct against efforts to change them, then these dogmas simply complete the sealing off of a vision from facts – and sealing off many people in lagging groups from the advances made available from other cultures around them, leaving nothing but the resentment-building and crusades on the side of the angels against the forces of evil – however futile or even counterproductive these may turn out to be for those who are the ostensible beneficiaries of such moral melodramas.”

I want to be clear, our world isn’t perfect, and there is more work that needs to be done. But our “incrementalism and step-by-step progress” that the Critical Race Theorists criticize, is just that, progress. So when I occasionally hear the word revolution, or the idea that America cannot exist if racism is ever going to end, I feel like people really have no idea what a miracle it is that we live in a society like we do. And it’s all made possible because of the concept of individualism. It’s also ironic because in a less free society, people wouldn’t even be able to voice those opinions.

Going Down A Familiar Road?

It hasn’t been that long since the 20th century where learned what happened when Nazi Germany rejected liberalism by dividing people into groups based on their nationality, or when Soviet Russia did the same based on class.

So when these CRT scholars say that all white people are privileged and racist, it’s incredibly controversial considering that the Jewish population is the most persecuted minority in European history, (a group that was also blamed for capitalism in Nazi Germany). Are they part of the privileged group? It doesn’t seem likely considering many of the real hate crimes committed today target people of Jewish descent. 27

Even in China, during the years of 1952-1968, communist leader Mao Zedong collectivized the agriculture industry with what he called “The Great Leap Forward.” It led to widespread famine and has been estimated to have caused around 30-40 million deaths. In 1966, in order to prevent his people from growing weary of communism, Mao started the “Cultural Revolution”. It sought to destroy the four “olds” of traditional ideas, cultures, habits, and customs, as well as purging the country of any traces of Capitalism and traditional values of Chinese society.(sound familiar?) Street names were changed, books were burned, Marxist propaganda depicted Buddhism as superstition, and dissenters were harassed, tortured, or murdered. Estimates of the deaths during the Cultural Revolution range from hundreds of thousands, to 20 million. 25

Lei Zhang, a University professor in North Carolina who lived through the revolution, has raised some alarms about the similarities he sees in America today: “The ideology, the CRT, I thought, this is very bad because it is the same as in China under Mao,” Lei proclaims. “The only difference is, in China Cultural Revolution it is your status in community, your class, but in CRT it is your identity, your race.” 22

He continues:

“When they tell kids, kindergarten, 5, 6 years old, that they are bad because they are in this race, or they are oppressed if they are in this group, and children cannot disagree, this is very bad because they cannot change their skin color or where they are from. They did not choose to be this race or that race, they are Americans…” “This is what happened under Mao and the Cultural Revolution. All the kids from very young are always told every day about you are in this status so you are low, and they teach to only love Mao and revolution. If you disagree or say something different they punish you, but not like men and women who may get punished, but they re-educate you to believe in Mao. You have no free thought.”

And although I admit some of this might seem a bit like fear mongering, many of these examples are eerily similar to some of the language coming from the social justice movement and critical theory today.

Here are a few examples of what a country veering in the direction of totalitarianism looked like to Hayek from his seminal work, The Road To Serfdom:

“Facts and theories must thus become no less the object of official doctrine than views about values. And the whole apparatus for spreading knowledge, the schools and the press, wireless and cinema, will be used exclusively to spread those views which, whether true or false, will strengthen the belief in the rightness of the decisions taken by the authority; and all information that might cause doubt or hesitation will be withheld.”

Spooky right? How about this one:

“The word truth itself ceases to have its old meaning. It describes no longer something to be found, with the individual conscience as the sole arbiter of whether in any particular instance the evidence (or standing of those proclaiming it) warrants a belief: it becomes something to be laid down by authority, something which has to be believed in the interest of the unity of organized effort, and which may have to be altered as the exigencies of this organized effort require it.

Conclusion

I realize I went on a book-length tangent here, but I want to tie it together with the last untruth of The Coddling.

The point I’m trying to make is that of all the well-intentioned things we are doing as a society, the social justice movement could end up making things astronomically worse.

The untruth that life is a battle between good people and evil people leaves us blind to the dangers posed by those intending to make things better.

Hitler, Marx, and Mao, didn’t think of themselves as evil. Hitler believed that his “heroic sacrifices” would bring about a 1000 year utopia. The Russian Revolution was started in an attempt to usher in a communist utopia. And Mao likely only wanted the best for his country.

So when people begin to divide individuals into categories of moral worth by classifying one as born with collective guilt, while the other is born with collective innocence, and they believe in the collectivist ethics that the ends justify the means, it’s easy to see how one might rationalize harmful behaviours and attitudes by thinking that they are acting for the greater good.

And even if I’m guilty of blowing this way out of proportion, I’d rather be embarrassed about being wrong than be right and not have been honest.

I’ll leave you with one last quote:

“Civilization is but a thin veneer stretched across the passions of the human heart. And civilization doesn’t just happen; we have to make it happen.”

Bill Moyers

Thanks for reading.

SOURCES:

- https://www.cato.org/survey-reports/state-free-speech-tolerance-america#overview

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/aug/14/ibram-x-kendi-on-why-not-being-racist-is-not-enough

- https://www.robindiangelo.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Anti-racism-handout-1-page-2016.pdf

- https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=AKqYlxMAAAAJ&hl=en

- https://edition.cnn.com/2021/01/21/health/fat-but-fit-study-scli-intl-wellness/index.html

- https://sph.umn.edu/site/docs/hewg/microaggressions.pdf

- https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-the-data-say-about-police-shootings/

- https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2017/10/05/4-race-immigration-and-discrimination/

- https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2015/10/21/its-all-about-the-denominator-and-rajiv-sethi-and-sendhil-mullainathan-in-a-statistical-debate-on-racial-bias-in-police-killings/

- https://www.creators.com/read/thomas-sowell/11/14/a-legacy-of-liberalism

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1982/05/03/single-parent-families-rise-dramatically/cc4afac4-2764-419e-8bda-66f14bad3dd0/

- https://www.phillytrib.com/metros/penn-law-professor-who-said-black-students-are-rarely-at-top-of-class-removed/article_a9b5d57e-2853-11e8-bdb6-536758baae17.html

- https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/13/opinion/critical-race-theory.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K4A-asV1EUU

- https://twitter.com/byronyork/status/1283372233730203651

- https://www.nevadacurrent.com/2021/01/21/las-vegas-charter-school-sued-for-curriculum-covering-race-identity/

- https://www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/civil-rights-reimagining-policing/a-lesson-on-critical-race-theory/

- https://nypost.com/2021/02/23/coca-cola-diversity-training-urged-workers-to-be-less-white/

- https://torontosun.com/life/ontarios-new-grade-9-curriculum-preaches-subjective-nature-of-mathematics

- https://www.tampafp.com/university-of-alabama-student-leads-the-charge-against-critical-race-theory-on-campuses/

- https://www.carolinajournal.com/news-article/n-c-college-professor-who-left-china-raises-alarm-over-woke-politics/

- https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/patients-and-families/cognitive-behavioral

- https://ckarchive.com/b/d0ueh0h67mpd

- https://www.reuters.com/world/us/many-americans-embrace-falsehoods-about-critical-race-theory-2021-07-15/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/rainerzitelmann/2020/07/27/anyone-who-doesnt-know-the-following-facts-about-capitalism-should-learn-them/?sh=8b034d63dc1e

- https://www.haaretz.com/us-news/.premium-jews-most-targeted-religious-group-in-2020-hate-crimes-fbi-says-1.10169147

- https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/09/19/controversy-over-paper-favor-colonialism-sparks-calls-retraction

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-uKabyhUid8

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minimal_group_paradigm

- https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2124&context=bclr

- https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2011/06/buy-happiness

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/ask-the-expert-A-Rubber-Ball-Thrown-On-The-Sea-631.jpg)

Recent Comments