“For prose is so humble that it can go anywhere; no place is too low, too sordid, or too mean for it to enter. It is infinitely patient, too, humbly acquisitive. It can lick up with its long glutinous tongue the most minute fragments of fact and mass them into the most subtle labyrinths, and listen silently at doors behind which only a murmur, only a whisper, is to be heard. With all the suppleness of a tool which is in constant use it can follow the windings and record the changes which are typical of the modern mind.”

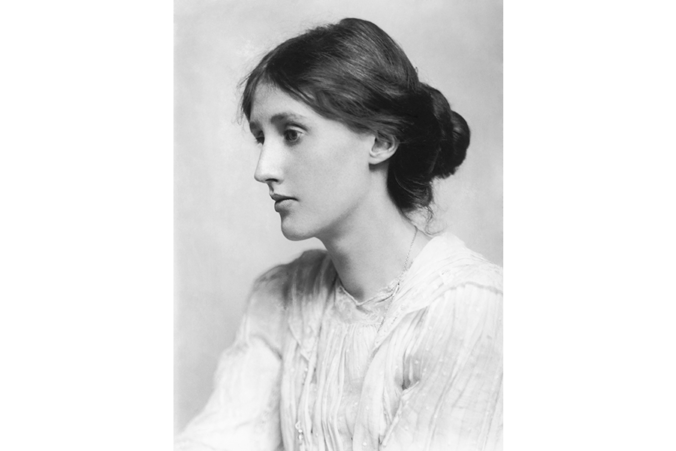

Virginia Woolf

That passage, from the extraordinary English writer Virginia Woolf, perfectly captures why her 1927 novel, To The Lighthouse, is quickly becoming one of my favourite books of all time.

She truly embodies her words, and her impressive talent and intelligence continue to floor me.

I recently read a quote that I liked from the author Michael Cunningham (who actually wrote a book inspired by Woolf) who said that: “She was doing with language something like what Jimi Hendrix does with his guitar. By which I meant she walked a line between chaos and order, she riffed, and just when it seemed that a sentence was veering off into randomness, she brought it back and united it with the melody.”

The truth is, I didn’t love To The Lighthouse immediately. It took a few days or even weeks of it marinating in my mind for me to realize that there was something about it that made it special; not one thing, but rather, a number of things – too many things in fact that I get overwhelmed when I think about them all.

Because the more I was thinking about the book’s language, the themes, the symbolism, the characters, and the context, the more I could feel the novel’s subtle but brilliant complexity unfolding. It contained all the makings of what I feel every great book should be, not just a piece of entertainment, or some story of a individual or experience; nor a difficult essay on some obscure topic. No. Like all great books do, To The Lighthouse contains both the universal and the particular, the themes are relevant and enduring, the language is beautiful, and the message is inspiring and affecting.

And not only that, but the authors life, the literary movement she belonged to, and the contribution she made to humanity, could each merit a blog post of their own.

That’s why this blog can be so difficult at times. I have so much to say about this book, but I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to do it justice.

It’s also funny because these are the types of books that I wish I could recommend to all my friends and family. I wish everyone could see the novel how I see it. Learn what I learned. But I’m confident many wouldn’t enjoy it. Because the book’s not really about anything. Nothing really happens. But at the same time, it’s about everything; life, family, time, art, knowledge, gender, desire, society, war, you name it. And it’s all packed into 190 pages!

I guess that’s why I like writing these posts, it’s my way of sharing these great books without having to nag people to read them.

However, I should preface that I’m still learning as I write. The conclusions and interpretations I make about the novel might be wrong to some. But I think there are some relevant and worthwhile pieces of wisdom here regardless. I also tried to organize it in a somewhat interesting and approachable way to the best of my abilities. And I apologize ahead of time for the length, Woolf has so many amazing passages that I just couldn’t leave out.

Structure and Plot

The plot of To The Lighthouse – if one can even call it a plot – centres around a family vacationing in the Isles of Skye in Scotland sometime between 1910 and 1920.

The book is divided into three parts: “The Window,” “Time Passes,” and “The Lighthouse.” Woolf herself described the structure of the novel as “two blocks joined by a corridor.”

The first section, “The Window,” takes place in a single day as we follow the seemingly mundane lives and internal thoughts of a family and the various house guests staying with them. They plan a trip to the lighthouse that is eventually abandoned, the adults take walks, the children play near the ocean, a woman paints outside, a young couple get engaged, and they all get together for a dinner party in the evening.

On the surface, it’s about exciting as a baked potato. But the beauty is in the details.

The middle section, “Time Passes,” is exactly what it sounds like. Ten years go by in which we get the poetic and haunting descriptions of the slow decay of the summer house. In addition, World War One happens, and it’s here we learn about the deaths of some of the characters. (They are written in short parenthesis without much of an explanation, as if signifying that human life is nothing more than a footnote compared to the enormous span and breadth of time.)

It reminds me of a quote from Ulysses that I like, where Joyce touches on the incomprehensible concept of time in relation to our fleeting existence: “Time’s ruins build eternity’s mansions.”

Lastly, in the third part of the novel, “The Lighthouse,” we find some of the characters returning to the summer house ten years later, and who finally make the trip to the lighthouse. The characters wrestle with their internal conflicts, the young woman who was painting her picture finally finishes it, and that’s pretty much it.

Woolf’s “Subtle Labyrinths”

With the very first line of the novel, the reader is thrown into a conversation between a mother and her son. The woman’s name is Mrs. Ramsay and she is responding to her son James’ inquiry of a possible trip to the lighthouse the next day: “Yes, of course, if its fine tomorrow, said Mrs. Ramsay.”

These first words in the novel are interesting. They are reminiscent of Molly Bloom’s famous soliloquy in James Joyce’s Ulysses, in which her first and last words of the chapter are “yes”:

“… and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes.”

According to her diary and letters to friends, Woolf had strong feelings about her contemporary. She called Joyce “Egotistic, insistent, raw, striking, and ultimately nauseating.” She also had this to say about Ulysses: “Never did a book so bore me.”

(Those are bold words considering Ulysses is regarded by many as one of the greatest novels ever written.)

But her word choice is suspect, and I think, deliberate. It’s as if she is responding, in her opinion perhaps, to Joyce’s failed attempt at an accurate internal female perspective.

Because like the first one, the last sentence in To The Lighthouse also begins with “yes”: “Yes…I have had my vision.”

And if you think that might be a coincidence, chapter two begins with the word “No,” and chapter three begins with “Perhaps.” But we will discuss their significance later on.

Now, before I go any further, I think it’s important to discuss the literary movement both Woolf and Joyce belonged to; because I can hear a particular voice in my head of someone I know who might be thinking: “Well, what if she meant nothing by those words, or that image, etc?”

And maybe that’s true of some books and authors, but I don’t think we have the liberty of being that naive when referring to Virginia Woolf. And hopefully by the end of this post you will agree.

Literary Modernism

Both Woolf and Joyce belonged to the literary movement called Modernism. In fact, both of their novels serve as touchstones of the movement itself.

Broadly speaking, Modernism, which began in the late 19th century and lasted until the mid 20th century, had numerous manifestations in philosophy, art, and architecture. But in literature specifically, the transition away from reliable narration, the use stream-of-consciousness writing techniques, the use of symbolism, and the idea that form follows function, characterized the movements most prominent features.

Up until this point in literary history, most authors felt that narrative form was best suited to representing real life as accurately and as realistically as possible.

But now, by rebranding what a novel was capable of, these authors were able to explore and experiment with form and structure to more accurately represent an authentic response to the global catastrophe of world war, the disillusionment of a rapidly changing world, and the new sensibilities that accompanied the transition.

This is from Encyclopaedia Brittanica:

“A primary theme of T.S. Eliot’s long poem The Waste Land (1922), a seminal Modernist work, is the search for redemption and renewal in a sterile and spiritually empty landscape. With its fragmentary images and obscure allusions, the poem is typical of Modernism in requiring the reader to take an active role in interpreting the text.”

This “active role of interpreting the text” couldn’t be more relevant than with Woolf’s To The Lighthouse. She was keenly aware of the power of symbolism and allusions to convey meaning.

Symbols like metaphor, allegory, and archetypes, help the reader visualize complex concepts and simplify themes. They also allow writers to discuss ideas in an efficient and artful way which gives readers a chance to add to the story with their own subjective inputs. Furthermore, symbolism allows a writer to approach a controversial theme in a more delicate manner.

In her essay, On being Ill, Woolf reveals something significant about the inherent deficiencies of words alone.

“…words seem to possess a mystic quality. We grasp what is beyond their surface meaning, gather instinctively this, that, and the other — a sound, a colour, here a stress, there a pause — which the poet, knowing words to be meagre in comparison with ideas, has strewn about his page to evoke, when collected, a state of mind which neither words can express nor the reason explain.”

The “knowing words to be meagre in comparison with ideas” is especially applicable here.

And keep that in the back of your mind, because I might not say exactly what I mean in the most efficient way possible, but I hope to leave some traces of intelligibility with which the reader can parse some kind of meaning.

The Theme of Gender

In To The Lighthouse, Woolf uses these metaphors and archetypes to weave a narrative around the gender norms in 20th century Britain.

She uses them to convey ideas about metaphysical concepts and how they influence and interact with one another; how through a lens of identity, for example, a person’s subjective views about life, death, art, time, and meaning, are interpreted.

The woman mentioned earlier, Mrs. Ramsay, is the archetypal representation of the traditional woman in Victorian England, and also, according to Woolf’s sister Vanessa, the perfect re-creation of their own mother.

Mrs. Ramsay’s encouraging words to her son at the beginning of the novel represent the conventional compassionate and nurturing tendencies that were expected of all women at the time.

But they are contradicted by the father, Mr. Ramsay, the stereotypical domineering, authoritarian, and masculine presence in the home.

“”But,” said his father, stopping in front of the drawing-room window, “it won’t be fine.””

Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay represent the reoccurring theme of the male vs female – objectivity vs subjectivity dichotomy in the novel:

“What he (Mr. Ramsay) said was true. It was always true. He was incapable of untruth; never tampered with fact: never altered a disagreeable word to suit the pleasure or convenience of any mortal being, least of all his own children, who, sprung from his loins, should be aware from childhood that life is difficult; facts uncompromising…”

Mrs. Ramsay, on the other hand, is willing to lie to her son to make him feel better: “But it may be fine – I expect it will be fine,” she says. And in response to his father’s contradictory words, six year old James thinks about grabbing a weapon and killing him. His mother, he thinks, is “ten thousand times better in every way.”

It’s early on in the novel that we experience the frequent perspective changes – which sometimes makes it difficult to know who is thinking and when. (Also, in case you missed it, Woolf uses James’ internal reaction to suggest that he has what Sigmund Freud would have called an Oedipal complex, where a boy competes with the father for the mother’s love. Woolf would have been familiar with the scientific theories of her day, and was often surrounded by some of the most prominent artists and intellectuals in England.)

When Mrs. Ramsay mentions the trip to the lighthouse again, Mr. Ramsay snaps at her:

“The extraordinary irrationality of her remark, the folly of women’s minds enraged him. He had ridden through the valley of death, been shattered and shivered; and now, she flew in the face of facts, made his children hope what was utterly out of the question, in effect, told lies. He stamped his foot on the stone step. “Damn you,” he said. But what had she said? Simply that it might be fine tomorrow. So it might.”

Woolf continues with Mrs. Ramsay’s reaction:

“To pursue truth with such astonishing lack of consideration for other people’s feelings, to rend the thin veils of civilization so wantonly, so brutally, was to her so horrible an outrage of human decency that, without replying, dazed and blinded, she bent her head as if to let the pelt of jagged hail, the drench of dirty water, bespatter her unrebuked.”

Another example of this dichotomy can be seen later on in the novel when Mrs. Ramsay is putting her daughter Cam and her son James to bed. There is a decorative pig skull hanging on the wall in their room and Cam wants her mother to take it down. James objects, and Mrs. Ramsay compromises by covering it with her shawl.

She comforts Cam by saying: “how lovely it looked now; how the faeries would love it: it was like a bird’s nest: it was like a beautiful mountain such as she had seen abroad, with valleys and flowers and bells ringing and birds singing and little goats and antelopes…”

To James, she says: “see, the boar’s skull is still there; they had not touched it; they had done just what he wanted.”

Even at their young age, the children adhere to Woolf’s portrayal of the feminine qualities of comfort and subjectivity and the masculine qualities of truth and objectivity.

It should be noted here that Mr. Ramsay’s field of study is metaphysics, a branch of philosophy that deals with abstract concepts such as being, knowing, cause, identity, time, and space. He is concerned with the truth and nature of reality, while his wife lives her reality; one is concerned with reason, the other with being.

Woolf goes on to describe Mr. Ramsay’s mind in great detail. She explains how he thinks in a linear fashion, comparing his intelligence to the letters of the alphabet: “his splendid mind had no sort of difficulty in running over those letters one by one, firmly and accurately, until it had reached, say, the letter Q. He reached Q. Very few people in the whole of England reach Q… Z is only reached once by a man in a generation.”

But his intellectual pursuits make him dreadfully insecure. He continuously thinks about his legacy and is troubled by the idea of being forgotten, on never reaching Z. He made one meaningful contribution to philosophy when he was younger but he fears his best days are behind him. He laments: “The very stone one kicks with one’s boot will outlast Shakespeare. His own little light would shine, not very brightly, for a year or two, and would then be merged in some bigger light…”

So as opposed to being portrayed as the strong, dependant, masculine figure, Mr. Ramsay appears weak and moody as he faces thoughts of his own mortality against the impending plague of time. “He was a failure, he repeated.” “He would never reach R. On to R, once more R…”

His response is to turn to his wife for emotional support:

“If he put his implicit faith in her, nothing should hurt him; however deep he buried himself or high, not for a second should he find himself without her.”… “It was sympathy he wanted, to be assured of his genius, first of all, and then to be taken within the circle of life, warmed and soothed, to have his senses restored to him, his barrenness made fertile, and all the rooms of the house made full of life…”

Mrs. Ramsay comforts him, as is her feminine principle, but she pays for it, much like Mr. Ramsay pays for his: “So boasting of her capacity to surround and protect, there was scarcely a shell of herself left for her to know herself by: all was so lavished and spent…”

Mrs. Ramsay not only provides support for her family, but for the whole male population, which she felt was her duty. We see the same thing in her interactions with the other characters, like Charles Tansley.

Mr. Tansley is a young man staying with the family who looks up to Mr. Ramsay. He is one of his “great admirers,” even mimicking his sentiment regarding the trip to the lighthouse: “”No going to the lighthouse James,” he said.”

Woolf describes Mr. Tansley doing what “he liked best – to be for ever walking up and down, up and down, with Mr. Ramsay, and saying who had won this, and who had won that, who was a “first rate man” at latin verses, who was “brilliant but I think fundamentally unsound”, who was undoubtedly the “ablest fellow in Balliol”…”

It’s indicative of the things Woolf likely would have been accustomed to in her own life. Men bragging about personal tastes and judgments, where confidence in conviction is the only work required, this masculine behaviour that almost seeks to be challenged.

Mr. Tansley, like Mr. Ramsay, is also insecure. Together, they represents the unpleasant qualities that Woolf attributes to masculinity. They are insensitive, egotistical, selfish, and totally dependant on other peoples’ high opinion of themselves – especially from the women, whom they rely on for emotional support and ego stroking.

The children all dislike Mr. Tansley, but Mrs. Ramsay, defends him, saying: “Yes, he did say disagreeable things…It was odious of him to rub this in, and make James still more disappointed; but at the same time, she would not let them laugh at him.”

Woolf explains why Mrs. Ramsay puts up with such male behaviour and how she justifies it:

“she had the whole of the other sex under her protection; for reasons she could not explain, for their chivalry and valour, for the fact that they negotiated treaties, ruled India, controlled finance; finally for an attitude towards herself which no woman could fail to feel or to find agreeable, something trustful, childlike, reverential…”

When Mrs. Ramsay and Mr. Tansley take a walk together, for example, she goes out of her way to flatter him and show him compassion despite his shortcomings. In response, Mr. Tansley feels sense of pride in being near her beauty.

Mrs. Ramsay finds meaning in being kind and generous and by capturing the ephemeral nature of life in the small pleasantries it has to offer.

But she also exhibits some traces of the masculine qualities, and despite suffering under them, she is complicit with the traditional gender roles of her day.

She thinks all women should be just like her, she thinks that: “an unmarried woman has missed the best of life.”

We also get a glimpse into what motivates her:

“For her own self-satisfaction was it that she wished so instinctively to help, to give, that people might say of her, O Mrs. Ramsay! dear Mrs. Ramsay . . . Mrs. Ramsay, of course! and need her and send for her and admire her? Was it not secretly this that she wanted…”

She relishes this attention and she organizes a dinner party where “the whole of the effort of merging and flowing and creating rested on her.”

She acts as the mediator, guiding the conversation, and dishing out the food. During the dinner she muses on the fleeting hours of the day and the way moment seems to transcend time:

“Everything seemed possible. Everything seemed right. Just now (but this cannot last, she thought, dissociating herself from the moment while they were all talking about boots) just now she had reached security; she hovered like a hawk suspended; like a flag floated in an element of joy which filled every nerve of her body fully and sweetly, not noisily, solemnly rather, for it arose, she thought, looking at them all eating there, from husband and children and friends; all of which rising in this profound stillness…Nothing need be said; nothing could be said. There it was, all round them. It partook, she felt, carefully helping Mr. Bankes to a specially tender piece, of eternity; as she had already felt about something different once before that afternoon; there is a coherence in things, a stability; something, she meant, is immune from change, and shines out (she glanced at the window with its ripple of reflected lights) in the face of the flowing, the fleeting, the spectral, like a ruby; so that again tonight she had the feeling she had had once today, already, of peace, of rest. Of such moments, she thought, the thing is made that endures.”

After the dinner is finished she ponders on the past and what it means to her:

“Yes, that was done then, accomplished; and as with all things done, became solemn. Now one thought of it, cleared of chatter and emotion, it seemed always to have been, only was shown now and so being shown, struck everything into stability. They would, she thought, going on again, however long they lived, come back to this night; this moon; this wind; this house: and to her too.”

Parallels In My Life

As I was reading this book, I couldn’t help but notice similarities to my own life. I think that’s part of the allure of reading; this discovery of our resemblance to the rest of humanity; this sense of belonging and realizing that there is likely nothing that you’ve ever felt or thought that hasn’t been felt or thought by someone else.

One of the reasons why I write this blog is to leave a legacy behind. The things that Mr. Ramsay struggles with – that he will inevitably be forgotten – is all too familiar to me. I often feel that some kind of preservation of my self is what gives my life meaning.

I also see other similarities concerning this masculine and feminine dichotomy.

I work in a male-dominated trade as a machinist. My work leaves no room for subjective interpretation. I’m forced to adhere to rigid tolerances where something is either right or wrong, without ambiguity.

My wife on the other hand works in a predominately female trade as a nurse. She’s a care-giver who’s proper bedside manner is a crucial part of her job. She is there to comfort her patients, and besides the actual medicine – which can most definitely be right or wrong – compassion seems like a requirement for her position.

Often I get so caught up in a book, or a piece of writing that I forget to smell the roses as it were. It’s usually my wife who reminds me to appreciate a sunset, or with a gentle touch draws my attention toward the beauty of a moment.

That’s why this quote from the novel, where Mrs. Ramsay is thinking about her husband, rang so true to me:

“Indeed he seemed to her sometimes made differently from other people, born blind, deaf, and dumb, to the ordinary things, but to the extraordinary things, with an eye like an eagle’s. His understanding often astonished her. But did he notice the flowers? No. Did he notice the view?”

In fact, most of the women in my life have embodied these tendencies more than the men.

I remember when I was younger my mom would sometimes sing that song, “We Are Family”, by Sister Sledge, but instead of singing “I got all my sisters and me,” she would say all our names in the chorus. I imagine I would have rolled my eyes back then, feeling embarrassed for the both of us, but now that moment feels extra special to me. It was her way of appreciating the fleeting moment of happiness, and she’s helped me remember it by doing so.

Another example is how my wife (and even the majority of women I know) enjoy shopping and making their homes beautiful. I’m always the one saying “we don’t need this, or we don’t need that.” But I’ve come to appreciate that the spaces they create and the things they surround themselves with gives their lives meaning. It’s about treasuring the moment and feeling inspired by the beauty around them.

But it’s interesting how we still adhere to some of these gender roles, despite most of them being arbitrary. Maybe it’s because they provide a path for us to navigate the complex social world we find ourselves in. It’s much easier to conform to them than risk the exposure of the great unknown; we find safety and security following the way others have paved before us.

But sometimes the bravest thing we can do is make our own path, and sometimes we find that others will follow in our footsteps.

Which brings us to Woolf’s character who embodies this message.

Lily Briscoe

In contrast to Mr. and Mrs. Ramsay, who occupy the stereotypical gender norms, Lily falls somewhere in between. She represents the third option, the “perhaps”; the androgynous.

She also represents the person who Woolf tried to be in real life. Lily’s final words at the end of the novel after she finishes her painting,”Yes, I have had my vision,” can be interpreted as an allusion to Woolf’s novel itself.

Lily resists the rigid binary of male and female gender roles. She challenges the male hegemony and seeks to find a sense of her own individuality.

As an aspiring painter, she is aware of the restrictions placed on women who wanted to pursue a career in art or writing. The voice of Mr. Tansley echos in her mind throughout the novel: “Women can’t write, women can’t paint.”

She struggles to understand how Mrs. Ramsay can overlook the tyrannical masculine traits around her, something she can’t do herself. And as she sits and paints outside, she looks into the window at Mrs. Ramsay, who has the protection of her role as caregiver and comforter that surrounds her in her house, safe from the uncertainty that Lily feels outside by breaking from the traditional roles, insecure and fearful that someone will judge her.

Because of that, Lily is unable to finish her painting of Mrs. Ramsay, she is confused and unsure of her opinion of her.

In the last part of the novel, after which a decade passes in which we learn of Mrs. Ramsay’s death, Lily tries again to paint the picture. This time she suffers from interruptions from Mr. Ramsay, who embodies the dominating male patriarchy that is keeping her from truly expressing herself.

But she perseveres, trying to find her meaning, wrestling with ideas regarding time and being, and how to manifest them:

“One wanted, she thought, dipping her brush deliberately, to be on a level with ordinary experience.”

She also questions her motives for painting. Here we can discern a faint echo of Mr. Ramsay:

“She looked at the canvas, lightly scored with running lines. It would be hung in the servants’ bedrooms. It would be rolled up and stuffed under a sofa. What was the good of doing it then…”

This next quote is my favourite of the novel. Here Lily has an epiphany about Mrs. Ramsay. It makes her realize that she was wrong about her, that she was only trying to make life meaningful in the only way she knew how.

“What is the meaning of life? That was all — a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years. The great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark; here was one. This, that, and the other; herself and Charles Tansley and the breaking wave; Mrs. Ramsay bringing them together; Mrs. Ramsay saying “Life stands still here”; Mrs. Ramsay making of the moment something permanent (as in another sphere Lily herself tried to make of the moment something permanent) — this was the nature of the revelation. In the midst of chaos there was shape; this eternal passing and flowing (she looked at the clouds going and the leaves shaking) was struck into stability. Life stands still here, Mrs. Ramsay said. “Mrs. Ramsay! Mrs. Ramsay! she repeated. She owed this revelation to her.”

Mrs. Ramsay finds meaning in capturing memories to cherish in the future; Mr. Ramsay finds meaning in his work outlasting time, lingering as long as possible in the past; and together, they inspire Lily to embrace the present and capture the moment through art. She understands that it’s not about the end product, but the act in and of itself.

Lily discovers something that reminds me of a quote I read recently:

“Individuality of expression is the beginning and end of all art.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Woolf’s Feminism

On the surface, we might think of the obvious symbol of “The lighthouse” as masculine, the phalic, the beacon of objective reality; and “The window”: feminine, the transparent, the subjective view of the beholder.

Additionally, the chapter “Time passes,” might be seen as a symbol of its own: the middle section, the Lily Briscoe, the corridor that connects them both. It represents the progression of society, the new woman; the evolution of culture and society into a more inclusive and balanced harmony.

But these symbols become more complex when we view them in light of Woolf’s deeper and more philosophical meanings.

In an article in The International Journal of English Language, Literature, and Humanities, titled, Feminism in Virginia Woolf’s Theory and its Reflection in Her Work To The Lighthouse, Sunayana Khatter points out three classifications of feminism:

1. Women demand equal access to the symbolic order. Liberal Feminism, Equality.

2. Women reject the male symbolic order in name of difference. Radical Feminisim. Feminity extolled.

3. Women reject the dichotomy between masculine and feminine as metaphysical.

Khatter argues that Woolf’s writing belonged to the third classification.

What does that mean?

This is what I think – Woolf knew that the cultural and societal norms and traditions regarding gender influence our understanding and expression of subjective metaphysical concepts.

To put simply, that gender is a social construct, and that it can restrict and oppress those that are expected to conform to their prescriptive roles.

Except Woolf felt that things didn’t have to be that way.

To clarify, as Khatter writes, To The Lighthouse is not an argument for “the flight from fixed gender identities, but a recognition of their falsifying metaphysical nature.”

So through the lens of time, say, a theme that permeates the entire novel, Woolf describes how the male and female characters find different modes of expression and meaning in the face of the tragic ephemerality of life, which are tied to their respective genders, but, according to Woolf, they don’t have to be.

The Androgynous

To prove that this dichotomy of masculinity and femininity was wrong, Woolf gives us these complex character sketches, and uses her stream-of-consciousness writing style to show us, in real-time, instances of the incongruous nature of the characters thoughts and actions regarding these rigid binaries.

Mr. Ramsay comes across as rude and short-tempered, but he’s insecure and dependant on others for support. Lily Briscoe points out these contradictions: “why he needed always praise; why so brave a man in thought should be so timid in life; how strangely he was venerable and laughable at one and the same time.”

Similarly, Mrs. Ramsay, who occupies the traditional role of caretaker and comfort giver, finds meaning in her life by creating memories and environments in which people are happy, supported, and encouraged.

We see Mrs. Ramsay as both submissive and subservient, putting the feelings of others above her own, and at the same time, we see how strong, capable, and somewhat selfish and authoritarian she really is.

Woolf was showing us that her characters are much more multi-dimensional than the gendered expectations society puts on them.

And we can think of the lighthouse in the same way, it’s not only an objective beacon, taken to be a symbol of the physical world, representative of masculinity. It also represents the feminine principles, it gives life. Just as the lighthouse serves to illuminate darkness and discover truth, it also, much like Mrs. Ramsay does herself, provides safety and prevents disaster.

Here Woolf gives us this symbolic marriage of Mrs. Ramsay and the lighthouse:

“…and pausing there she looked out to meet the stroke of the Lighthouse, the long steady stroke, the last of the three, which was her stroke, for watching them in this mood always at this hour one could not help attaching oneself to one thing especially of the things one saw; and this thing, the long steady stroke, was her stroke. Often she found herself sitting and looking, sitting and looking, with her work in her hands until she became the thing she looked at – that light, for example…She looked up over her knitting and met the third stroke and it seemed to her like her own eyes meeting her own eyes, searching as she alone could search into her mind and her heart, purifying out of existence that lie, any lie. She praised herself in praising the light, without vanity, for she was stern, she was searching, she was beautiful like that light.”

Lily embodies this concept of rejecting the metaphysical as masculine and feminine most of all, not only in terms of her characters actions, but symbolically. She chooses to reject the idea that women can’t be artists and discovers her own identity and individuality.

By drawing a line in the middle of her paining at the end of the novel, she captures Woolf’s theory of androgyny and its nature of balance and unity.

In her novel, A Room of One’s Own, Woolf elaborates on the importance of this idea:

“that the androgynous mind is less distinguishing than the single-sexed mind; that the androgynous mind is resonant and porous; that it transmits emotion without impediment; that it is naturally creative, incandescent and undivided.”

And although she is specifically speaking about art in the next passage, I think Woolf’s words can help us better understand ourselves by questioning the lens through which we view the world, and ask ourselves if we are mindlessly adhering to unhelpful, arbitrary, or even harmful gender norms.

“It is fatal for anyone who writes to think of their sex. It is fatal to be a man or woman pure and simple; one must be woman-manly or man-womanly…Some collaboration has to take place in the mind between the woman and the man before the art of creation can be accomplished. Some marriage of opposites has to be consummated.”

Contemporary Feminism

Woolf was considered to be a part of the first-wave of feminism. And her contribution to the movement, and the inspiration she had on the women of the second-wave of feminism of the 1960’s and 70’s, can still be felt today.

But as I was writing this post, I couldn’t help shake the feeling that feminism is a bit of a dirty, loaded word nowadays.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I think everyone, regardless of gender, should be afforded the same basic human rights. And I also think feminism, especially during the first and second waves, was absolutely, one-hundred percent necessary.

Because of their efforts, our society has made incredible progress since Woolf’s time.

Domestic violence has dropped 67% in the last few decades, while sexual violence has been cut in half.

According to statistics Canada, women make up 47% of the workforce now. In 1950, that number was around 25%.

Women are also more likely than men to have graduated high school, and more likely than men to have college or university qualifications.

And despite the common misconception that women only make 77 cents for every dollar a man earns, according to PolitiFact, research shows that number is closer to 94 cents. The initial figure was based on the average incomes of each gender, not taken from men and women with the same jobs. The jump from 77 to 94 is explained by factoring in men working longer hours on average, retiring later, and working more dangerous jobs.

There is obviously something missing to account for that 6% difference, but the data is weak. Discrimination, women’s reluctance to ask for raises, and other personality or biological differences might contribute, but they are difficult to measure.

In an article titled, “What Is The Problem With Feminism” author, Mark Manson, writes:

“Previous generations of feminists were willing to die in the trenches of getting women the right to vote, to go to college, to have an equal education, for protection from domestic violence, and workplace discrimination, and equal pay, and fair divorce laws. This generation’s tribal feminists’ trenches are that of The Feelings Police — protecting everyone’s feelings so that they never feel oppressed or marginalized in any way.”

These new “tribal feminists” remind me of that episode of The Simpsons, where Lisa wants to play football.

“That’s right,” she says, “A girl wants to play football. How about that?”

The coach, Ned Flanders responds, “Well, that’s super-duper, Lisa. We’ve already got four girls on the team.”

Lisa asks, visibly disappointed, “you do?”

“Ah huh. But we’d love to have you onboard!”

“I dunno… football’s not really my thing. After all… what kind of civilized person would play around with the skin of an innocent pig?!”

Well, actually, Lisa, these balls are synthetic! And for every ball you buy, a dollar goes to Amnesty International!

“I gotta go.” she says, starting to cry.

Here’s some more wisdom from a cartoon character:

“Anytime someone calls attention to the breaking of gender roles, it ultimately undermines the concept of gender equality by implying that this is an exception and not the status quo.” – knuckles the Enchidna

Because today, women can be anything, and do anything. And I’m not saying there aren’t sexist, and misogynistic people out there – and there is an obvious problem with crime – but perhaps it’s not a systemic issue of the patriarchal society like it once was.

It seems to me like the people like Lisa, trying to fight for a meaningful change with the best intentions in mind, look up to people in the past who were brave and who stood up for what they believed in. The ones that are celebrated as heroes and remembered, much like how we remember Woolf now.

The problem is that these courageous figures of the past fought against measurable inequalities. Discrimination was black and white in many ways during the first two waves of feminism. But now, as Mannon writes:

“the hardest part about it is that there’s no easy metric in the social arena for what is equal and what is not. If I fire three employees and two of them are women, is that equality? Or is that sexism? You can’t say unless you know why I fired them. And you can’t know why I fired them unless you can get inside my brain and understand my beliefs and motivations.”

And what’s ironic about contemporary feminism, is that me being a man, and quoting a man while discussing these topics, some people will undoubtedly think that my opinion is somehow invalidated because of my gender. A feminist might claim my views are a symptom of the patriarchy and therefore discredit them. I might even be called a misogynist. But isn’t preventing discrimination based on gender the whole point of feminism?

If they cared about equality, wouldn’t the fact that men serve 63% longer prison sentences than women for the same crime be an appropriate topic to tackle? Or perhaps why over 90% of prison inmates are male? Or why men are more likely to commit suicide?

Instead, we get headlines like this one: “”Upward-thrusting buildings ejaculating into the sky” – do cities have to be so sexist?“

The thing is, is that Woolf would have disagreed with that gendered type of thinking. Attributing singular masculine symbolism to an object would, in her opinion, have been a step backward for feminism.

I want to be clear, I’m not saying we live in a perfect word where discrimination doesn’t exist, it most certainly does. Also, I’m positive that there are activists, scholars, and thinkers out there making meaningful contributions to better the lives of women. But for every one of them, how many more are trying to find solutions to problems that don’t exist?

Maybe we don’t need to reinvent the wheel. There have been plenty of brilliant minds in the past that have made much more meaningful (and relevant) contributions to ameliorating the suffrages of women than these “feminists” of today.

Like the extraordinary Virginia Woolf for example, who will never know how wrong she was when she said:

“I will not be “famous,” “great.” I will go on adventuring, changing, opening my mind and my eyes, refusing to be stamped and stereotyped. The thing is to free one’s self: to let it find its dimensions, not be impeded.”

Thanks for reading.

Recent Comments