“It is only a novel… or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language”

Jane Austen

There is a common belief that Jane Austen is a woman’s novelist. There are some that even consider her books to be “chick-lit.” While it’s true I’m sure, that many of her readers are women that adore her books for their romance, marriage plots, and witty and humorous depictions of Regency England, Austen is so much more than that.

She provides her reader with a sort of emotional education. And perhaps I can only speak for myself when I say she draws your attention to the flaws of your own character, while at the same time making you conscious of the feelings of others around you.

I don’t know how many times I’ve related to one of her “bad” characters, only to have Austen show me why I might be in the wrong. Her stories are universal in that special way that makes the mundane seem astonishing, and the banal seem didactic.

Austen has shown us that her words are timeless, and that the human emotions she writes about: envy, pity, remorse, jealousy, and love, etc., are things we all feel, independent of race, class, age, or gender.

Compared to other great 19th century novelists, her books are largely devoid of the serious broader cultural and social events of her day. They occupy a vacuum of space, frozen in time, in which more strenuous and philosophical discussion is left to others. But that’s what makes them so relevant. It’s the lack of cultural context, the universality of their characters, and their relatable human behaviours that transcend temporal boundaries, that draws in new readers, generation after generation.

A few particular topics I’ve noticed Austen touch on with exceptional accuracy are Manners and Morality. The following quotes are from various characters in Mansfield Park. Each of them is unique in that they paint a particular moral picture. Each of them is defined by their value systems as opposed to more traditional descriptions of their character traits.

This is from Edmund Bertrum, one of the novels “good” characters:

“(A clergyman) has the charge of all that is of the first importance to mankind, individually or collectively considered, temporally and eternally, which has the guardianship of religion and morals, and consequently of the manners which result from their influence”

The following is referring to Maria Bertram, one of the “bad” ones:

“(she) was beginning to think matrimony a duty; and as a marriage with Mr. Rushworth would give her the enjoyment of a larger income than her father’s, as well as ensure her the house in town, which was now a prime object, it became, by the same rule of moral obligation, her evident duty to marry Mr. Rushworth if she could.”

This next one is referring to Maria’s sister, Julia Bertram, who, like her sister, shows us why the “duty” and “obligation” the’ve been raised with are so hollow and superficial.

“The politeness which she had been brought up to practice as a duty made it impossible for her to escape; while the want of that higher species of self-command, that just consideration of others, that knowledge of her own heart, that principle of right which had not formed any essential part of her education, made her miserable under it.”

And this is from Mrs. Norris, who is not just “bad,” but quite possibly the most annoying and unbearable characters I’ve ever encountered in any novel:

“but I shall think her a very obstinate, ungrateful girl, if she does not do what her aunt and cousins wish her— very ungrateful, indeed, considering who and what she is.”

The “ungrateful girl” Mrs. Norris is referring to is Fanny Price, who was moved at a young age to live with her rich aunt and uncle to relieve some of the financial burdens on her own family. Fanny is considered lower class because of that, and is treated as such by her aunts and cousins. Even her uncle claims that Fanny and his children “cannot be equals. Their rank, fortune, rights, and expectations, will always be different.”

Her cousin Edmund is the only character that treats Fanny with any respect and dignity. As we already know, he believed that manners (manners perhaps being defined as the expectations of social conduct) should be a direct consequence of morals, particularly those provided by religion.

Conversely, the others demonstrate that good manners, whether from cultural traditions, social norms, class distinctions, etc., don’t always correspond to what’s “right.” For instance, they treat Fanny worse than they would someone of higher social rank, and they don’t think there is anything wrong with that.

In Austen’s day, a certain decorum was observed by the upper class in order to maintain a sort of conformity and harmony within the community, and failure to respect that was considered uncivilized. In Mansfield Park, Austen was satirizing her society by showing how immoral these standard of propriety can be. She was illustrating how the established social conducts and customs of a given society don’t always correspond to sound ethical principles.

And nowhere is this phenomenon more prevalent than our own culture, where the line between right and wrong is razor thin.

I read an article recently from the New York Times that told of a young white girl who had been caught on video using a racial slur when she was just 15 years old. Years later, after she was accepted into university, the video re-surfaced. Consequently, she lost her spot on the cheerleading team, and she was forced to withdraw from the school. The man responsible for releasing the video, “wanted to get her where she would understand the severity of that word.” When the man was questioned about it, he said he had no regrets; he was glad to have had the opportunity to teach someone a lesson.

And these aren’t rare occasions either, read the comments on any controversial news story. You’d be amazed at the moral righteousness some people display. And often times it’s coming from people with compassion, empathy, and tolerance as their main ideological drivers.

It never ceases to amaze me how people fighting for tolerance and inclusivity can be so intolerant. Many of them are are vengeful, vindictive, angry, and unforgiving, and who feel other people deserve harsh punishments because of their ignorance, or some momentary lapse in their judgments.

Sure, they might be appearing to have good intentions, to combat racism or misogyny, for example, but they’ve been blinded by their own indignation for it to do any good.

Because shame works differently than guilt. When we are shamed, we look inward toward ourselves. We tie whatever it is we did to our identities. It’s an egocentric response to humiliation. Whereas guilt is an empathetic response toward others as a result of our actions. Do you see the difference? Guilt is positive, based on the responsibility of our actions, and shame is negative, based on unhelpful and often harmful self-reflection. It’s even been observed in this study, that people suffering from guilt are better at identifying the emotions of others than those suffering from shame.

Additionally, public shaming often results in the disproportionate punishment relative to the “crime” committed. And what’s worse is that whoever is doing the shaming is encouraged by claims of moral superiority. They feel good about themselves because they are behaving in a manner that conforms to their idea of a “just” society.

They’re just like the Bertram Sisters and Mrs. Norris, who believe they have moral high ground, despite not demonstrating the least bit of genuine goodness.

It’s like these people have been taught to identify right from wrong in some aspects, but not how to respond to them with tolerance or remission? How many of them would turn the proverbial cheek in response to some injustice? How many would voluntarily walk in the shoes of those being chastised, to seek forgiveness and understanding as opposed to retribution?

From what I can see around me, not many.

And I’m no saint either, believe me. Because this is where I had to stop writing. This always seems to happen to me; my pesky brain start to really think about what I’m saying. I was half-way through writing this piece when I realized that I was displaying the same righteousness and moral superiority that I was criticizing.

When I put myself in the shoes of the man who released the video, I learned that we have used the very same moral justifications for some things. He believed that the ends justified the means. He felt that a hard lesson learned was the price to pay for some positive change in the world.

And I know how he feels. The following quote is from none other than Jane Austen:

“There are people, who the more you do for them, the less they will do for themselves.”

Jane Austen

I couldn’t agree more with her, and because of that, I have certain negative views regarding welfare and government aid. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think they should be abolished, but I definitely think in some cases they are doing more harm than good. By minimizing welfare, there would undoubtedly be some human cost and suffering, but in the end I think our society would benefit greatly and be stronger because of it.

That’s not an opinion that’s received very well by the opposite side of the political spectrum. To them, I’m unsympathetic, immoral, and lacking empathy. But it’s the same moral reasoning as before.

Perhaps the only difference is that, I’m not married to my idea, nor do I have the intention of causing harm to anyone. I only want to help. I believe in the resiliency of human nature, and I believe that adversity and hardship lead to growth.

Austen would have agreed, she said herself there is “advantages of early hardship and discipline, and the consciousness of being born to struggle and endure.”

In Mansfield Park, Mariah and Julia Bertram, lacked such an advantage. They were brought up to be “distinguished for elegance and accomplishments,” which led to them having “no useful influence… no moral effect on the mind.”

And for all you socialists out there in favour of a welfare state, Karl Marx even warned that “The democratic petty bourgeois, far from wanting to transform the whole society in the interests of the revolutionary proletarians, only aspire to a change in social conditions which will make the existing society as tolerable and comfortable for themselves as possible,” thereby, placating the revolutionary consciousness and preventing a socialist overthrow.

I don’t want to start a political debate, I only want to point out how blurred this line of morality can get.

But when you try to understand someone else’s perspective, you can learn a lot about them. You learn about what they value. Because it’s our value systems that dictate our moral justifications.

It’s easy to say that the characters in Mansfield Park are “bad,” because we can see what they value. Things like money, status, and propriety, are more important to them than treating others fairly, or of marrying for love.

But things get complicated when the values become more nuanced. Lets go back to my idea of welfare. I place high value on individualism, liberty, and order, because I believe they are crucial components of any functioning society. A government with too much power, and effecting too much economic intervention, will inevitably lead to tyranny, because in my opinion, man is not morally perfectible.

The man who released that video on the other hand, values something different entirely. I don’t think it would be a stretch to assume that he, and people with similar views as himself, places high value on fairness, equality, and compassion. And maybe I would place more emphasis on them too If I had the same life experiences as them. Who knows. But it’s only by understanding each other and being patient and tolerant of different value systems, that we have any chance of making positive changes in the world.

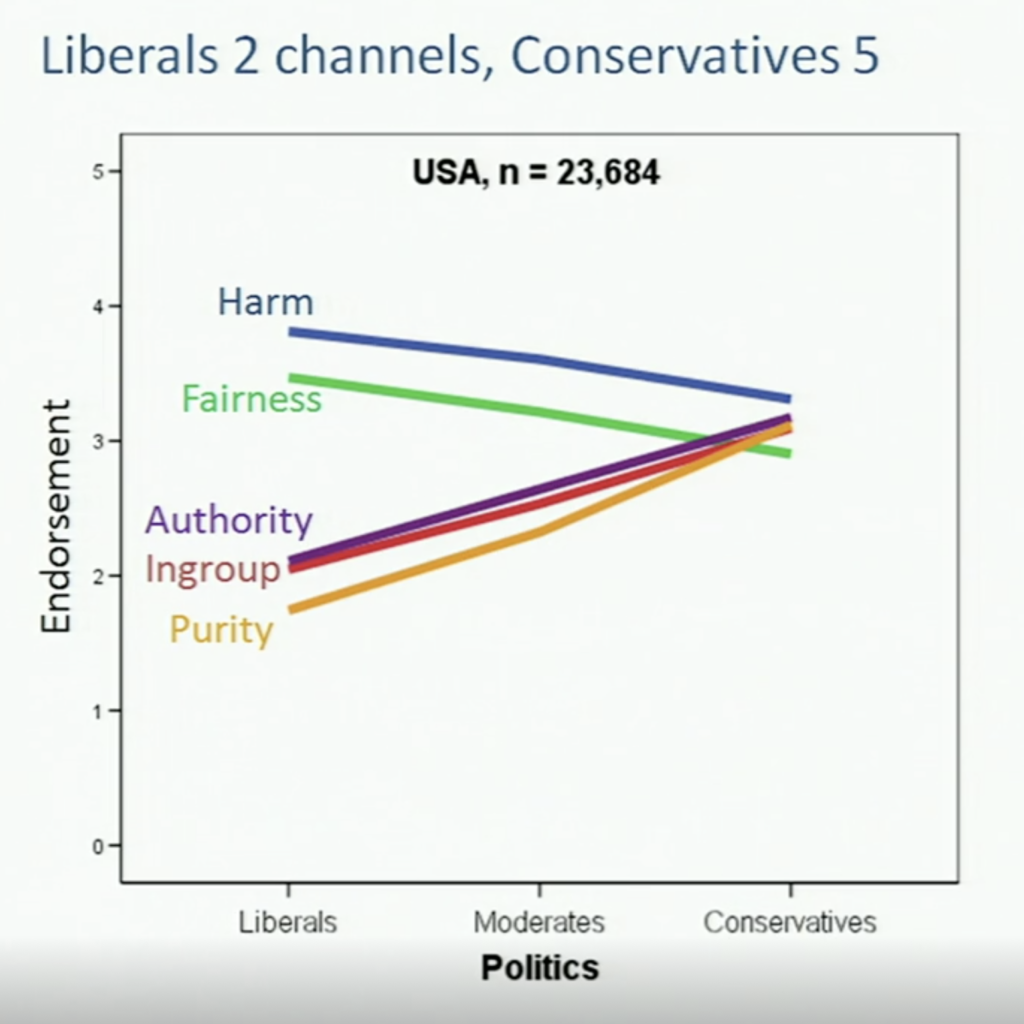

A social psychologist named Jonathan Haidt, who specializes in moral psychology, proposed what he called the “Moral Foundations Theory.” He believed that the variations in our moral reasoning comes from six “modular foundations.” They are: Care/Harm, Fairness/Cheating, Loyalty/Betrayal, Authority/Subversion, Sanctity/Degradation, and Liberty/Oppression. Haidt argued that our political views depend on where we placed our endorsements on such foundations. The following graph is a good visual representation of his ideas.

I think it’s helpful to identify what our foundations are, but the problem is, as I see it, is not what they are, but how strong our convictions of them are.

So what can we do about it?

Some of the most common solutions are to engage in social discourse, to talk things out. But that’s hard because people’s emotions get in the way of meaningful apprehension of opposing ideas. Many of us are reluctant to put in the effort to understand how and why people can think so differently than us. Not to mention, it’s difficult to try to understand another point of view, especially when we attach so much of our egos to our own.

That’s where literature comes in.

When you read, you’re disconnected from the world, and you’re able to observe life from wildly different perspectives; from the writers who have perfected the craft of conveying human nature to their reader. It’s just you and the author, no judgements, and no ego.

In addition, books offer us an alternative to the mindless superficiality of social media. We’re able to step out of our echo chambers, where we can be exposed to the thoughts and feelings of people we otherwise might disagree with.

Few things are more morally instructive than that.

And perhaps it’s from reading that Austen suggests we might “soon learn to think more justly, and not owe the most valuable knowledge we could any of us acquire – the knowledge of ourselves and of our duty, to the lessons of affliction…”

By doing so, we don’t have to let our own personal experiences dictate our moral foundations; we can learn from other people’s experiences as well.

And as for the people we’re unable to reform or encourage to see things from a different point of view, Austen recommends we let “their tempers become their punishment.” Because people who are angry, vindictive, or malevolent, probably aren’t the happiest of people.

Thanks for reading.

I’ll leave you with one last quote, but remember, these are Austen’s words, not mine:

“The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid.” …

Jane Austen

Leave a Reply