“It is something to be able to paint a particular picture, or to carve a statue, and so to make a few objects beautiful; but it is far more glorious to carve and paint the very atmosphere and medium through which we look, which morally we can do. To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of arts.”

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau was an American poet, essayist, naturalist, and philosopher, born on July 12th, 1817 in Concord, Massachusetts.

Thoreau was a fervent abolitionist, a passionate writer and speaker for the movement, as well as a conductor involved in the Underground Railroad.

He is also famous for having spent a night in jail for the non-payment of a poll tax on the grounds that the money was being used to fund a war against Mexico. It inspired him to write his essay titled, “Civil Disobedience,” which would influence such activists and prominent figures as Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr.

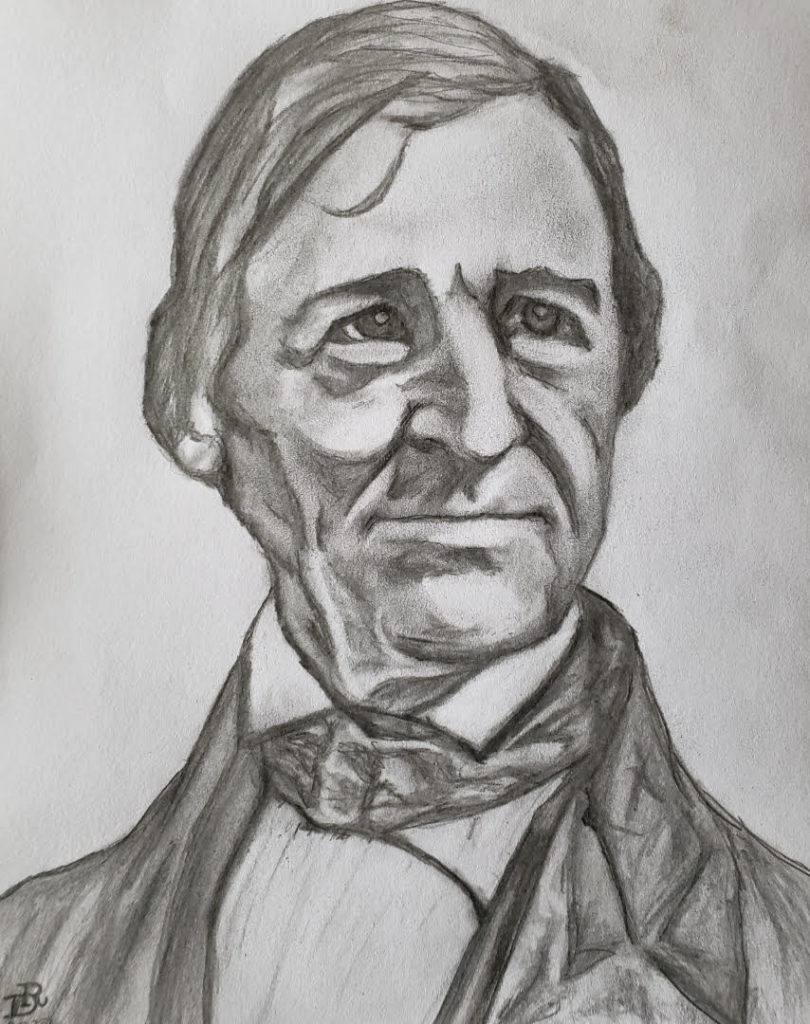

But Thoreau is most commonly remembered as a major figure of the Transcendentalist movement, which included writers like Margaret Fuller, Walt Whitman, and his friend and mentor, Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Transcendentalists aimed to discover the nature of reality by investigating the process of thought rather than the objects of sense experience. They believed in the purity of the individual, of self-reliance, and the capabilities of man to generate insights intuitively, free from the corruption of institutions and society.

Thoreau’s most famous work, Walden, published in 1854, is an account of his experiences living alone in a cabin he built for himself near Walden Pond, just outside of Concord. He lived there for two years and two months as a sort of a self-experiment and spiritual journey.

This is from Walden:

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.”

Some argue that Walden is the product of a self-obsessed narcissist, that Thoreau was a hypocrite, his ideas arrogant, and his prose dry and condescending. It’s true, you’ll soon learn, that he had strong opinions about society and how he thought we should live, but we shouldn’t let that discount any positive messages that we might find in his words.

It could be simply that his most butt-hurt critics are those on the receiving end of some uncomfortable truths that Thoreau pointed out.

Regardless, most find it hard to argue against the positive impact he’s had on the world. The following is taken from Analysis and Notes on Walden: Henry Thoreau’s Text with Adjacent Thoreauvian Commentary by the scholar, Ken Kifer:

“Thoreau’s careful observations and devastating conclusions have rippled into time, becoming stronger as the weaknesses Thoreau noted have become more pronounced … Events that seem to be completely unrelated to his stay at Walden Pond have been influenced by it, including the national park system, the British labor movement, the creation of India, the civil rights movement, the hippie revolution, the environmental movement, and the wilderness movement. Today, Thoreau’s words are quoted with feeling by liberals, socialists, anarchists, libertarians, and conservatives alike.”

Our current society could use more people like Thoreau right now, those who are capable of crossing such hard political lines.

Thoreau himself, in some of the first pages of Walden, admits that his philosophies are not a one-size-fits-all. He believed that each person should take from his ideas their own personal messages, that what might be true for him, might not be true for everyone. He hoped “that none will stretch the seams in putting on the coat, for it may do good service to him whom it fits.”

So lets slip our arms through the sleeves of some of the wisest words of the 19th century, and see if we haven’t outgrown them yet.

1.

“A man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.”

Henry David thoreau

Thoreau said this in 1854, long before the hyper-consumerist trends of the 20th century.

These were his some of his observations while walking down the main street in Concord:

“The Traveller had to run the gauntlet…Signs were hung out on all sides to allure him; some to catch him by the appetite, as the tavern and victualling cellar; some by the fancy, as the dry goods store and the jeweller’s; and others by the hair or the feet or the skirts, as the barber, the shoemaker, or the tailor.”

I wonder what he would say today about our billboards, television advertisements, and internet ads.

I bet it would sound something like this:

We are constantly nudged, persuaded, or rather charmed even, by those who hold our best interest as secondary importance, those whose icons we wear proudly on our shirts, unpaid and unwittingly, those who ruthlessly wrap their chubby and greedy fingers around our necks, 5,000 times a day, and beckon us with a contemptible smile and nod toward that mean and insidious term, delicately clothed in wool, that we call comfort.

We are coerced with promises of easy living with items of luxury and extravagance, but according to Thoreau, they only weigh us down with their burdens.

They have power over us, he warns, we spend so much of our valuable time and effort preserving them that we find ourselves neglecting more important aspects of our lives. It’s this emotional attachments to our stuff that Thoreau says denies us true wealth.

2.

“I had three pieces of limestone on my desk, but I was terrified to find that they required to be dusted daily, when the furniture of my mind was all undusted still, and threw them out the window in disgust.”

HEnry DAvid Thoreau

This reminds me of a scene in the movie American Beauty, where Kevin Spacey and Annette Bening, a husband and wife who’s marriage has gotten stale and distant, begin to have a rare moment of intimacy. As Spacey inches toward Bening, whispering nostalgic memories of their former affection, Bening comments that Spacey’s beer he is holding is almost spilling onto the couch. “It’s a $4000 sofa” she protests, “upholstered in italian silk.” Spacey, who is visibly upset, stands up and responds with the unforgettable line: “It’s just a couch! This isn’t life! This is just stuff. And it’s become more important to you than living. Well, honey, that’s just nuts.”

How many of you have placed an emotional attachment to objects at the expense of a loved one, of living in the moment, of truly appreciating what life has to offer, or of leaving the furniture of your minds undusted?

I know I have.

And it gets even more complicated when we understand that, as consumers, we are brainwashed into thinking that our possessions are an extension of our identity. It’s bad enough to love an object so much that our emotional well-being is tied to it, but we go one step further and blend our self-worth with what we own.

Thoreau offers us some advice: “Sell your clothes and keep your thoughts.”

3.

“The fault-finder will find faults even in paradise. Love your life, poor as it is. You may perhaps have some pleasant, thrilling, glorious hours, even in a poorhouse. The setting sun is reflected from the windows of the almshouse as brightly as from the rich man’s abode.”

Henry David Thoreau

And It isn’t just our culture’s shallow material obsessions that Thoreau criticizes, he tells us how society represses the depth of our conversations as well.

4.

“Just so hollow and ineffectual, for the most part, is our ordinary conversation. Surface meets surface. When our life ceases to be inward and private, conversation degenerates into mere gossip. We rarely meet a man who can tell us any news which he has not read in a newspaper, or been told by his neighbour; and, for the most part, the only difference between us and our fellow is, that he has seen the newspaper, or been out to tea, and we have not.”

Henry David Thoreau

Replace “newspaper” with Facebook article, tweet, or the newest Netflix show, and it’s more relevant than ever.

5.

“In proportion as our inward life fails, we go more constantly and desperately to the post-office. You may depend on it, that the poor fellow who walks away with the greatest number of letters, proud of his extensive correspondence, has not heard from himself this long while.”

Henry David Thoreau

Replace “letters” here with likes and you have our plugged-in societies dependance on external validation and lack of self-esteem.

6.

“Most men, even in this comparatively free country, through mere ignorance and mistake, are so occupied with the factitious cares and superfluously coarse labours of life that its finer fruits cannot be plucked by them.”

HEnry David Thoreau

This one reminds me of a George Eliot quote that I try to explain to my wife when she asks me to do chores while I’m reading:

“Only those who know the supremacy of the intellectual life──the life which has a seed of ennobling thought and purpose within──can understand the grief of one who falls from that serene activity into the absorbing soul-wasting struggle with worldly annoyances.”

Just kidding. She would probably roll her eyes out of her head if I said that.

Thoreau isn’t saying not to do chores either, he was himself fond of “honest, manly, toil,” he is just saying that we create many of our own problems, which only distract us from what is meaningful.

He encourages us to shift our perspective, however slightly, so we can appreciate the simple things in life that we tend to ignore when we get corralled into routine.

Take a deep breath. Contemplate. Listen. Find solitude.

Thoreau believed in the power of Nature to inspire in us spiritual self-reliance. We don’t need to complicate our lives with unnecessary complexities, Thoreau argued, we only need “Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity.”

7.

“…in this part of the world it is considered a ground for complaint if a man’s writings admit of more than one interpretation. While England endeavours to cure the potato-rot, will not any endeavour to cure the brain-rot, which prevails so much more widely and fatally?”

Henry David Thoreau

8.

The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them.

Henry david thoreau

Can you see now why Thoreau’s critics disliked him so much? I agree that some of his words come across as self-righteous and preachy, but in our age of consumerism-everyone-gets-a-trophy-victimhood-cancel-culture, it’s important to be reminded of all the things that we could be doing wrong that might be hurting us and our ability to be happy. They can be hard pills to swallow, but there is something so empowering in shouldering blame instead of putting it on others.

But don’t worry, not all he says is negative.

9.

“If the day and the night are such that you greet them with joy, and life emits a fragrance like flowers and sweet-scented herbs, is more elastic, more starry, more immortal- that is your success. All nature is your congratulation, and you have cause momentarily to bless yourself.”

Henry David Thoreau

10.

“I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.”

Henry David Thoreau

11.

“A single gentle rain makes the grass many shades greener. So our prospects brighten on the influx of better thoughts. We should be blessed if we lived in the present always, and took advantage of every accident that befell us, like the grass which confesses the influence of the slightest dew that falls on it; and did not spend our time in atoning for the neglect of past opportunities, which we call doing our duty. We loiter in winter while it is already spring.”

Henry David Thoreau

12.

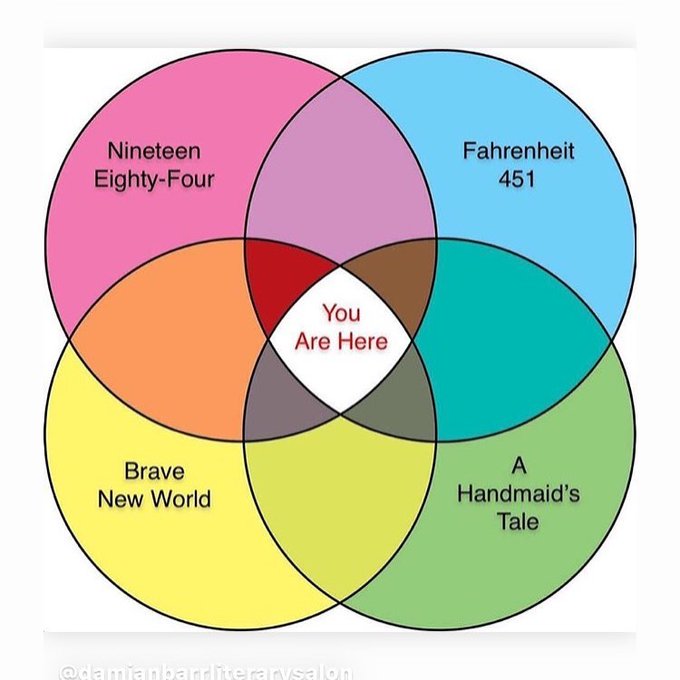

“It is never too late to give up our prejudices… What everybody echoes or in silence passes by as true today may turn out to be falsehood tomorrow, mere smoke of opinion, which some had trusted for a cloud that would sprinkle fertilizing rain on their fields.”

Henry david thoreau

This is a quote that our increasingly politically polarized world needs to hear daily, including myself; to not have a death-grip on your convictions. Emerson put it well when he said: “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

How often, when we have an opinion, do we look for evidence to validate our initial claim instead of learning about the opposition’s, and thereby, either strengthening our own argument by noticing its weaknesses, or changing our minds by acknowledging its strengths?

Not often. Most of us prefer the deafening insulation of an echo chamber instead.

These next few quotes are what make Thoreau extra awesome in my opinion. But I might be a tad biased.

13.

“Most men have learned to read to serve a paltry convenience, as they have learned to cipher in order to keep accounts and not be cheated in trade; but of reading as a noble intellectual exercise they know little or nothing; yet this only is reading, in a high sense, not that which lulls us as a luxury and suffers the nobler faculties to sleep the while, but what we have to stand on tip-toe to read and devote our most alert and wakeful hours to.”

14.

“For what are the classics but the noblest recorded thoughts of man? They are the only oracles which are not decayed, and there are such answers to the most modern inquiry in them as Delphi and Dodona never gave.

Henry David Thoreau

15.

“It is not all books that are as dull as their readers. (Haha) There are probably words addressed to our condition exactly, which, if we could really hear and understand, would be more salutary than the morning or the spring to our lives, and possibly put a new aspect on the face of things for us. How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book! The book exists for us, perchance, which will explain our miracles and reveal new ones. The at present unutterable things we may find somewhere uttered. These same questions that disturb and puzzle and confound us have in their turn occurred to all the wise men; not one has been omitted; and each has answered them, according to his ability, by his words and his life.”

I especially love these quotes because Thoreau is not only articulating beautifully some of the strongest arguments in favour of reading the classics, but we consider him a classic author now, and we read his books for the same reason that he read others before him.

Sadly though, he died at the early age of 44 from Tuberculosis, so we will never know how many more contributions he might have made to the literary world.

Emerson wrote this after his death, reminding us that despite Thoreau being gone, his memory will live on forever:

“The country knows not yet, or in the least part, how great a son it has lost. . . . His soul was made for the noblest society; he had in a short life exhausted the capabilities of this world; wherever there is knowledge, wherever there is virtue, wherever there is beauty, he will find a home.”

Thanks for reading.

Recent Comments