“Wherever they burn books, they will also, in the end, burn human beings.”

Heinrich Heine

That was written by the German Poet in 1821, in his play Almansor. It was a reference to the burning of the Qua’ran during the forced conversion of Muslims to Christianity in Spain in the 15th century.

Taken out of context, Heine’s ominous words are commonly misinterpreted to be a prediction of the Holocaust. He wasn’t a prophet, he just understood that: “thought precedes action as lightning precedes thunder…” He understood that repressing and destroying opposing religious texts would culminate in the destruction of the people that adhere to those religions.

Heine would make a more chilling prediction in 1834. This time however, there was no risk of it being misconstrued: “A play will be performed in Germany which will make the French Revolution look like an innocent idyll.”

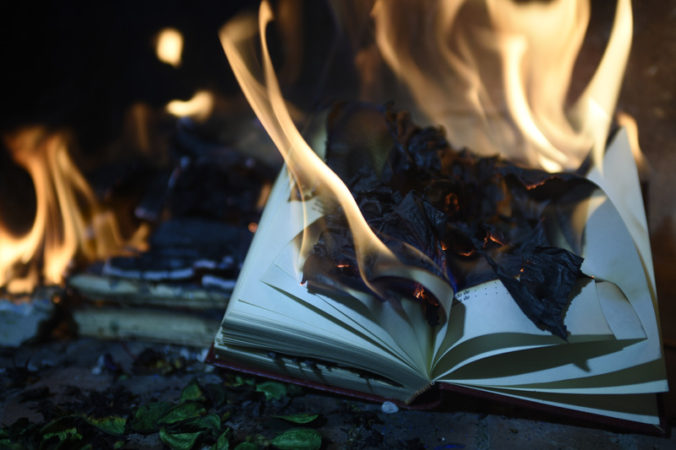

A hundred years later, In 1933, the German Student Union would set the stage for Heine’s play. They would conduct a nationwide book burning campaign. They would target books and materials that were opposed to Nazi ideologies, and anything they deemed to be: “Un-German.”

They were trying to synchronize German culture and language with the ideologies of the Nazi Party.

Joseph Geobbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, said at one of the public burnings: “The soul of the German people can again express itself. Those flames not only illuminate the final end of an old era; they light up the new!”

A decade earlier, something similar was happening in the newly formed Soviet Union.

In 1922, soon after the USSR was established, the Main Administration for Literary and Publishing Affairs was created. Its function was to censor any works of art or literature that they felt were harmful to their communist ideologies.

Books, for example, that dealt with themes of class struggle and food shortages were censored to prevent peasant uprisings. They also banned religious propaganda, and other “politically incorrect materials.”

“If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.”

Haruki Murakami

The horrors of totalitarianism in Europe in the 20th century, would inspire the English author George Orwell to shift the focus of his writing towards politics. He would start with the satirical allegory Animal Farm, in 1945.

Four years later, he would publish his legendary novel, 1984.

Written as a cautionary tale, 1984 is an unrelenting story of total government control, censorship, mass surveillance, violent oppression, and the hopeless, forceful submission to power.

The main character, Winston Smith, works for the “Ministry of Truth”. His job is to doctor photos and censor newspaper clippings so that they align with the Party’s ever-changing political agenda. Orwell sums up the Party’s philosophy:

“Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present, controls the past”

George Orwell

Fun Fact! Orwell’s wife Eileen worked in the Department of Censorship in the Ministry of Information in London.

Censorship and language are major themes in the novel. Words like “unperson” and “doubleplusgood” are examples of the new language forced upon working class citizens, called Newspeak. It was created as a means to restrict vocabulary, limit self-expression, and inhibit thought.

Orwell explains the sinister purpose of using censorship and language to manipulate and control:

“The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.”

George Orwell

He elaborates on that idea in the novel by explaining how 2+2=5 can become objective truth if the Party desires it to be.

“And what was terrifying was not that they would kill you for thinking otherwise, but that they might be right. For, after all, how do we know that two and two make four? Or that the force of gravity works? Or that the past is unchangeable? If both the past and the external world exist only in the mind, and if the mind itself is controllable-what then?”

George Orwell

Orwell’s books, and even his name, carry on today as a warning to us. “Orwellian” is an adjective that describes a situation or idea that threatens the security of an open and free society.

Which is why it’s disturbing to realize that some parts of 1984 are still so relevant today. Think: Edward Snowden, government mandated restrictions of free speech, and an increasingly militarized police force.

Four years after 1984 was published, the American author Ray Bradbury would publish his own dystopian novel called Fahrenheit 451. The title gets its name from the temperature at which paper catches fire.

Bradbury wrote the novel to express concerns of potential book burnings in his own country during the rise of McCarthyism.

The protagonist of the novel, Guy Montag, is a “fireman” who’s job it is to find and burn books (which gradually became unpopular in the futuristic society anyway). The government eventually banned them. The reason given was that books were confusing and difficult to read, which was upsetting to the people.

While on the job one day, Montag witnesses a woman who chooses to die with her massive book collection. It causes him to reflect:

‘‘There must be something in books, things we can’t imagine, to make a woman stay in a burning house; there must be something there. You don’t stay for nothing.”

Ray Bradbury

Montag becomes curious as to why they are burning the books and he steals a few to take home to read. He questions the governments motives and quits his job. Unable to get support from his drugged-up, screen-obsessed society, he goes on the run. He meets stragglers like himself, likeminded people who all have the common goal to revive their culture through literature.

The city was bombed shortly after Montag escaped. Thats some pretty heavy symbolism, if you’re into that sort of thing.

“Do you know why books such as this are so important? Because they have quality. And what does the word quality mean? To me it means texture. This book has pores. It has features. This book can go under the microscope. You’d find life under the glass, streaming past in infinite profusion. The more pores, the more truthfully recorded details of life per square inch you can get on a sheet of paper, the more ‘literary’ you are. That’s my definition anyway. Telling detail. Fresh detail. The good writers touch life often. The mediocre ones run a quick hand over her. The bad ones rape her and leave her for the flies. So now you see why books are hated and feared? They show the pores in the face of life.”

Ray Bradbury

Margret Atwood’s The Handmaids Tale, written in 1985, is another dystopian portrayal of an oppressive government. The novel is set in the not-so-distant-future of the United States, in a totalitarian state called Gilead.

The novel focuses on the brutal patriarchal society and the trials of the subjugated women who persevere despite their relentless sufferings.

Following the same formula as Orwell and Bradbury, books are illegal in the fictional Gilead.

“Knowing was a temptation. What you don’t know won’t tempt you.”

Margaret Atwood

There is one more noteworthy book that is frequently grouped with the others in the genre: Aldous Huxley’s 1932 novel, Brave New World.

The citizens in Huxley’s story are not violently forced into submission by their oppressors, instead they are active participants in the states control over them.

The year is 2450, the people are happy and content. They have no responsibility, no families, no children. Babies are developed in test tubes. They are genetically modified and phychologically conditioned from birth to fit into their predestined roles in society. They have been indoctrinated into embracing consumerism, mindless entertainment, sexual promiscuity, and drug use.

“And if ever, by some unlucky chance, anything unpleasant should somehow happen, why, there’s always soma to give you a holiday from the facts. And there’s always soma to calm your anger, to reconcile you to your enemies, to make you patient and long-suffering. In the past you could only accomplish these things by making a great effort and after years of hard moral training. Now, you swallow two or three half-gramme tablets, and there you are. Anybody can be virtuous now. You can carry at least half your morality about in a bottle.”

Mustapha Mond, one of the ten World Controllers who governs the “World State, explains their objective: “No pains have been spared to make your lives emotionally easy- to preserve you so far that is possible, from having emotions at all.”

The government also filters and censors information from academic institutions. This is Mond’s reasoning behind rejecting “a masterly piece of work”:

“It was the sort of idea that might easily decondition the more unsettled minds among the higher castes—make them lose their faith in happiness as the Sovereign Good and take to believing, instead, that the goal was somewhere beyond, somewhere outside the present human sphere; that the purpose of life was not the maintenance of well-being, but some intensification and refining of consciousness, some enlargement of knowledge..”

The World Controllers don’t just use censorship and pleasure to control, they use something called “hypnopedia,” or sleep teaching. It’s the underlying source of everyone’s prejudices and ideologies. It works by having a recording of repeated words and suggestions broadcasted through speakers while the children sleep.

“Till at last the child’s mind is these suggestions, and the sum of the suggestions is the child’s mind. And not the child’s mind only. The adult’s mind too—all his life long. The mind that judges and desires and decides—made up of these suggestions. But all these suggestions are our suggestions…Suggestions from the State!”

The novel’s plot follows two people as they go on a holiday from the city to a reservation outside civilized society. There are still small traces of primitive man in these secluded villages.

They meet a man there named john (everyone will call him the Savage). They find out his mother was raised in civilized society but was lost and left on the reservation for 20 years. She gave birth to her son and raised him herself, something that hadn’t been done in the World State in centuries.

The Savage grew up worshiping primitive gods. He grew up reading Shakespeare, he grew up with tradition, language, ritual, fear, shame, anger and guilt. He grew up with everything that was kept from people in civilized society.

It wouldn’t be a very convincing dystopian novel if books weren’t banned. Mond justifies their absence: “There was always the risk of their reading something which might undesirably decondition one of their reflexes.”

John was able to discover the power of language that the rest of society was being deprived of:

“He hated Popé more and more. A man can smile and smile and be a villain. Remorseless, treacherous, lecherous, kindless villain. What did the words exactly mean? He only half knew. But their magic was strong and went on rumbling in his head, and somehow it was as though he had never really hated Popé before; never really hated him because he had never been able to say how much he hated him. But now he had these words, these words like drums and singing and magic. These words and the strange, strange story out of which they were taken (he couldn’t make head or tail of it, but it was wonderful, wonderful all the same)–they gave him a reason for hating Popé; and they made his hatred more real; they even made Popé himself more real.”

When john and his mother are found, they are taken back to the city. John is treated like a circus animal, something to be stared at.

John has a breakdown and makes a scene as he tries to get people to snap out of their soma filled stupors. He gets apprehended and has a discussion with Mustapha Mond.

The savage asks why the people don’t read Shakespeare.

“Because it’s old; that’s the chief reason. We haven’t any use for old things here.”

“Even when they’re beautiful?”

“Particularly when they’re beautiful. Beauty’s attractive, and we don’t want people to be attracted by old things. We want them to like the new ones.”

“That’s the price we have to pay for stability. You’ve got to choose between happiness and what people used to call high art. We’ve sacfrificed high art.”

The savage gets fed up with to the fruitless discussion in which Mond seems to have all the answers. His response at the end of their conversations is one of the novels most memorable quotes:

“But I don’t want comfort. I want God. I want poetry. I want real danger. I want freedom. I want goodness. I want sin.”

Conclusion.

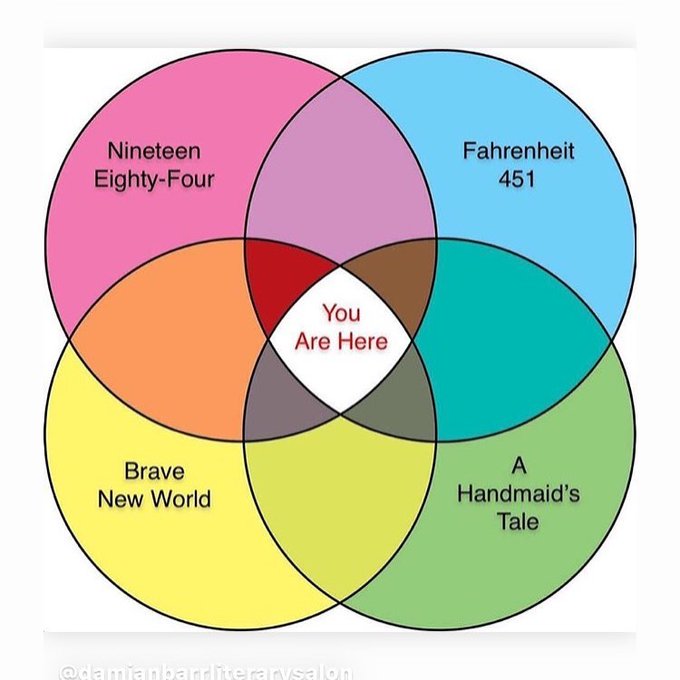

These Dystopian works of fiction take societies to their extremes in an effort to expose their flaws. They act as distant marks on the horizon. If we can see ourselves heading in their direction, even a little bit, we need change our course.

Huxley would write in 1958, that the ideas he expressed in his novel were approaching faster than he had initially anticipated. He would die a few years later in 1963.

I can’t imagine what he would think now.

I think he would be shocked at our society’s dependence on consumerism and convenience. Our lives revolve around abundance, comfort, ease, instant gratification, social media, and pop culture. We’re dumbing ourselves down with easy dopamine. We’re a culture that is obsessed with technologies that hinder our ability to think.

We don’t need a tyrannical government to censor our language and culture, we’re doing it to ourselves. It’s something the author of The Gulag Archipelago understood:

“Without any censorship, in the West fashionable trends of thought and ideas are carefully separated from those which are not fashionable; nothing is forbidden, but what is not fashionable will hardly ever find its way into periodicals or books or be heard in colleges. Legally your researchers are free, but they are conditioned by the fashion of the day.”

Aleksandr solzhenitsyn

We are the villains in Huxley’s story. Someone else may be dictating the terms, but we’re accepting them with open arms. Bradbury puts it even more bluntly:

“You don’t have to burn books to destroy a culture, just get people to stop reading them.”

Ray Bradbury

According to the Official Journal of American Academy of Paediatrics, an average child is exposed to 40,000 advertisements a year on television alone. They estimate that 3000 ads can be viewed in a single day on the internet, television, billboards, and magazines combined.

If you want an eye-opening deep dive into the subject of marketing and public relations, I would recommend watching the four part BBC documentary, called The Century of the Self. You can watch it on YouTube, i’ll put the link here. It talks about how governments and corporations have used Freud’s theories and psychological techniques to control people in a time of mass democracy and individualism.

Heres a quick summary:

“To many in politics and business, the triumph of the self is the ultimate expression of democracy, where power has finally moved to the people. Certainly, the people may feel they are in charge, but are they really? The Century of the Self tells the untold and sometimes controversial story of the growth of the mass-consumer society. How was the all-consuming self created, by whom, and in whose interests?” -BBC publicity.[6]

We’re living in our own type of dystopia. But we can do something about it. We can take advantage of the freedoms that we still have. Reading is redemptive and literature is morally instructive. It increases our capacity for empathy and allows us greater freedoms of expression.

“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

NELSON MANDELA

During Nelson Mandela’s 27 year imprisonment, it’s been said that he relied on Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations to help him persevere.

“Do not read, as children do, to amuse yourself, or like the ambitious, for the purpose of instruction. No, read in order to live.”

Gustave Flaubert

Lets hear from Heine one last time, who reminds us why these dystopian novels have so much to teach us. Without books and knowledge, whether from burning or banning, or by choosing not to read:

“You are nothing but the unconscious servants of those men of thought, who, often in modest silence, have plotted out all your doings in advance”

Heinrich Heine

Thanks for reading.

Leave a Reply